We couldn’t find a seat on the Washington Metro. In truth, we couldn’t see the Metro station, just a mass of humanity.

This gathering challenged the notion of enormous. The moment was historic.

Dumb luck came to our aid. A city bus hissed to a stop at the curb, and my friend and I hopped aboard, joined by a couple hundred of our new best friends. The atmosphere crackled with joy, solidarity and diesel fumes. I nearly busted out with “99 Bottles of Beer on the Wall.”

The driver seemed to catch our enthusiasm and peppered us with questions about the Women’s March. What time, where, how long would it last? She smiled realizing her shift would end before the speakers began, and I still wonder if she made it.

Nearly five hundred thousand of us convened on the National Mall, and expressed our heart-felt objections concerning the newly elected president. We marched as one.

By the way, no one violently attacked the halls of government. Though, if memory serves, I did flip off the Trump Hotel.

In October, 1969, 250,000 opponents of the Vietnam War descended upon Washington DC. In an event called Moratorium Day no one violently attacked the halls of government.

In the swelter of a 1963 Washington summer, Dr King convened the “Poor People’s” March on Washington. 250,000 Americans petitioned their government for a voting rights bill. No one even considered attacking the halls of government.

In the Spring and Summer of 1932 during the depth of the Great Depression, somewhere around 20,000 desperate men, some with their families in tow, marched on Washington DC as part of the Depression-era Bonus Army. For their trouble the marchers were attacked by Douglas McArthur, and an army detachment, who instead, burned out the shanties of the desperate. Again, no one attacked the halls of government.

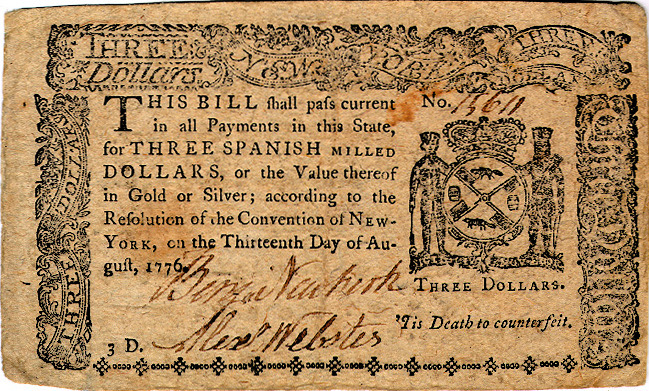

On March 3, 1913, the day before the inauguration of Woodrow Wilson, nearly 10,000 women paraded down Pennsylvania Avenue promoting women’s suffrage. Though they were attacked by angry men along the route, not one woman attacked the halls of government.

Nearly 10,000 American’s joined Jacob Coxey’s Army in May of 1894. An extended economic depression caused mass unemployment, and the “Army,” demanded a public works bill to create jobs. Though the marchers reached the Capitol, and Coxey, himself leaped up the stairs to read his public works bill, the police opened up some heads, and the crowd dissolved. No one entered the Capitol.

Public protest is as American as baseball. The difference lies in our use of free speech. On January 6, 2021 a mindless, misguided, and dangerous mob hijacked the right to assemble, instead escalating into a violent attack on our center of government. There is no middle ground; this was an attempted coup to seize power.

We were correct in 2017, as were those in 1894, 1932, 1963, and 1968. Marchers were seeking “the blessings of liberty” within the rule of law. None of us ignored nor defiled the spirit of protest.

And that sense of heart-felt objection, to that president proved accurate.

Gail Chumbley is the author of the two-part memoir, “River of January,” and “River of January: Figure Eight.” Both titles available on Kindle.

gailchumbley@gmail.com