This post originally appeared in early 2016. Cassandra award?

A divided national party . . . voices of extreme rhetoric . . . an ugly, contentious primary season. Does this spell doom for two-party system?

Sounds modern, doesn’t it? But the year was 1860, and the party in question was founded by Thomas Jefferson, and shaped in the image of Andrew Jackson: The antebellum Democratic Party.

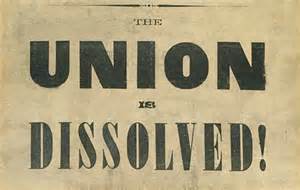

On the eve of Civil War, the future of the Union appeared in fatal doubt. Political leaders in the Deep South: South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Florida had all but washed their hands of the centrally powerful United States. Adding to the precarious atmosphere, a faction of Democrats in the North promoted a policy to permit slavery into the western territories under the principle of Popular Sovereignty, or direct vote. Others voices in the northern branch of the Democratic Party believed the Southern States should depart the Union in peace. And these pro-secession advocates became the most worrisome threat for Senate leader, Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, the leading Democratic candidate for the presidency in 1860.

Douglas found himself in a hell of a spot. He fervently burned to lead his party to the White House and save his nation, dangerously poised on the verge of civil war. As the principal heir to Senate leadership, Douglas had spent over twenty years in Congress working to stave off Southern secession, taking over when Kentucky Senator, Henry Clay, the “Great Compromiser” died. Clay had also spent most of his earlier career drawing up one concession after another in a noble attempt to preserve the Union. Eventually the effort wore him out, and Senator Douglas pick up the cause.

As far as Douglas was concerned, slavery wasn’t a moral issue, merely a bump in the road. The issue could easily be decided by the good folks migrating west. Douglas believed if settlers didn’t want slavery, they would decline to establish laws necessary for supporting the “peculiar institution.” But the Senator was wrong—dead wrong. Slavery had, by 1860 become an issue impossible to fix. And it was this miscalculation, underestimating the power of the slave issue, that the Illinois Senator imploded both his party, and his career.

The new Republican Party had organized six years earlier in Wisconsin, founded on one central principle—slavery would not extend into the western territories, period. And this new party spread quickly. Composed of splinter groups, this now fully unified alliance insisted that free labor was an integral component to a flourishing free market economy. The presence of slavery in sprouting regions of the West would devalue free labor, and undermine future commercial growth.

Now, don’t get me wrong, these Republicans did not sing Kumbaya or braid their hair. These men did not believe in equality between the races—they were not abolitionists. Economic principles drove their political platform, (Emancipation came later with the transformation of President Lincoln through the caldron of war).

For Stephen Douglas the approaching 1860 election meant vindication for his support of popular sovereignty, and reward for his faithful political service. And Douglas was no political hack. He fully understood the solvency of the Union lay in the delicate art of sectional balance, and his ascendancy to the White House as a Democrat would go a long way to placate the Southern hotheads. But this Illinois Senator failed, once again, to fully comprehend the temper of the nation, or of his own party. The era of seeking middle ground had passed—America’s course had been set toward industrial modernity with no place for an antiquated, barbaric labor system.

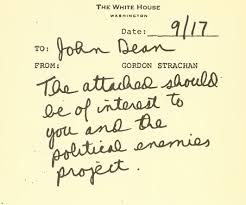

Charleston, South Carolina, was selected as the site of the 1860 Democratic convention. Chaos immediately broke loose on the convention floor. While Southern Democrats demanded strict, precise language guaranteeing the extension of slavery into the territories, Northern Democrats and those from California and Oregon pushed for Douglas’ popular sovereignty. This tense deadlock forced the latter faction to walk out and reconvene in Baltimore where party business could function.

Southern Democrats moved on without Douglas or his faction. In a separate, Richmond, Virginia convention, Southern Democrats proceeded to nominate Kentuckian John C. Breckinridge.

Back in Baltimore, Senator Douglas indeed gained the Democratic nomination, preserving his precious principle of local voters determining the western migration of slavery. Meanwhile, the Democrats in Richmond took a step further, adding the absolute protection of slavery to their platform. Middle ground had vanished.

Though a long shot, a third faction of the Democratic Party broke ranks with both Douglas supporters, and the Richmond faction. Calling themselves the “Constitutional Union Party,” this coalition nominated John Bell of Tennessee.

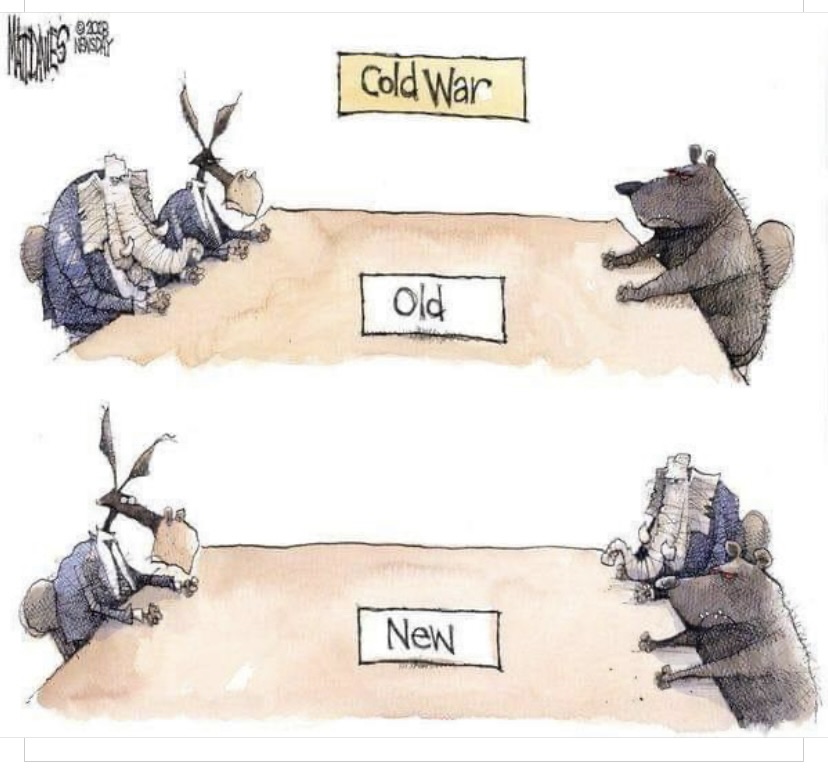

So what can we make of this 1860 fiasco today, in 2016? If I could attempt a bit of divination I would suggest that the political party that can present the most united front will prevail in the general election. If current Republican candidates continue to employ such wide-ranging, and scorching tones to their rhetoric, and stubbornly defend the innocence of their loose talk, the party may run head long into oblivion, as did the Democrats of 1860. If the roaring factions, currently represented by each GOP aspirant goes too far, the fabric of unity will shred, crippling the Republican’s ability to field serious candidates in the future.

Looking at the past as prelude much is at stake for the unity of the GOP. In 1860 party divisions nearly destroyed the Democrats, propelling the nation into a bloody civil war. And though Republicans at that time elected our greatest Chief Executive, Abraham Lincoln, the Democrats suffered for decades, marginalized as the party of rebellion. And even the best lessons left by the past are still forgotten in the heat of passion, by those who know better. (The Democrats shattered their party unity once again a hundred years later, splintered by the Vietnam War.) This is truly a cautionary tale for today’s turbulent Republican Party.

Zealots do not compromise, and leading GOP candidates are spouting some pretty divisive vitriol. Southern Democrats self righteously rejected their national party, certain it no longer represented them, and ultimately silenced the party of Jefferson and Jackson for decades. The lesson is clear for today’s Republicans. By tolerating demagoguery, extremism, and reckless fear-mongering in their field of contenders, the RNC may indeed face a similar demise.

Though it is true that no party can be all things to all citizens, malignant splinter groups should not run away with the party.

The American public demands measured and thoughtful candidates—and both parties are expected to field candidates of merit and substance.

We deserve leaders worth following.

As Senator Stephen Douglas refused to recognize that the political skies were falling around him, and his party, the modern Republican Party must not.

Gail Chumbley is the author of River of January, and River of January: Figure Eight a two-part memoir. Available on Kindle