2020.

Are the awful events of these last twelve months a once-off, bad patch of misfortune? Or is there a deeper explanation for the emergence of Trump, Covid, economic disaster, and civil unrest?

American History is steeped in a collection of pivotal moments, episodes that molded the nation’s continuing path. Can the events of 1776 stand alone as a turning point, or of 1865?

A long metaphoric chain links one scenario to the next, marked by momentary decisions, government policies, or beliefs, that surface at one point in time, and voila, America’s story fleshes out to the future.

Add chance circumstances to the narrative and predictability flies out the window.

Does 2020 stand alone as a singular event, or an inevitable outcome seeded somewhere in the past? Surely the march of history can be much like a chicken-egg proposition.

Mention 1776 and thoughts gravitate to the Continental Congress, the Declaration of Independence, and the emergence of General George Washington. But that struggle for freedom actually began at the end of the French and Indian War.

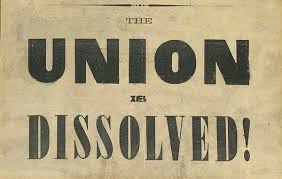

As for 1865, when the guns silenced at Appomattox Courthouse, Robert E Lee’s surrender affirmed America as a nation-state. But thirty years earlier, President Andrew Jackson’s administration had sparked the eventual war over the issue of slavery. Thinly disguised as the doctrine of states’ rights, the intractable argument of slavery festered. The “Peculiar Institution” is, was, and always be the cause of that bloodbath. In point of fact the fury of one man, John C Calhoun, South Carolina Senator, and former vice president, lit the fuse of war thirty years before Fort Sumpter.

As to the folly of Trumpism, arguably the roots are deeply burrowed in America’s collective past. Author, and historian Bruce Catton, wrote about a “rowdyism” embedded in the American psyche. Though Catton used that term in the context of the Civil War, his sentiment still resonates in the 21st Century, i.e., Proud Boys, and the like.

Closer to today, the Cold War seems to have honed much of the Far Right’s paranoia. The John Birch Society, for example, organized in the late 1950’s escalating anti-Communist agitation. Senator Joe McCarthy rode to fame on that same pall of fear, (with Roy Cohen at his elbow) only to fail when he went too far.

But the presidential election of 1964 seems to mark the most distinct shift toward the defiant opposition that fuels Trump-land.

Vietnam, in 1964 had not blown up yet. JFK had been murdered the previous fall, and his Vice President, turned successor, Lyndon Johnson was the choice of a grieving Democratic Party. The GOP fielded four major candidates in the primaries: three moderates and the ultra conservative, Barry Goldwater of Arizona. Senator Goldwater gained the nomination that summer with help from two men, conservative writer Richard Viguerie and actor Ronald Reagan.

Viguerie broke political ground through his use of direct mailing, and target advertising (what today is right wing news outlets). Reagan, once a New Deal Democrat, crossed the political divide and denounced big government in “The Speech,” delivered on behalf of Senator Goldwater. These two men believed Conservatism, and Laissez Faire Capitalism had been wrongly cast aside for liberal (lower d) democratic causes.

Their efforts struck a cord with legions of white Americans who felt the same resentment. The Liberal Media and Big Government from the Roosevelt years were Socialistic and anti-capitalistic. No urban problem, or racial strife or poverty appeared in their culdesacs or country clubs. And taxes to support Federal programs squandered and wasted personal wealth.

So many other issues shaped the modern New Right. Communism, the Cold War, Civil Rights, Vietnam, and progressive politics alienated the wealthy class.

But here’s the rub. Ultra conservative ideology is unworkable, an ideal that awards only a small, exclusive few, (today’s 1%). So 2020, and 2016 both have roots running deep in the core of the American experience.

2020 isn’t about this moment, not really.

Gail Chumbley is the author of “River of January,” and “River of January: Figure Eight,” a two-part memoir available at http://www.river-of-january.com and on Kindle. Also the stage plays, “Clay,” and “Wolf By The Ears” (the second in progress.)

gailchumbley@gmail.com