Balkanize: Division of a place or country into several small political units, often unfriendly to one another.

America’s founders meant education to flourish, as a vital part of our country’s longevity.

Designed to advance literacy, American public schools also curbed the rougher aspects of an expanding country. Since the earliest days of the Republic, centers of learning not only taught content, but other lessons like cooperation, and self control. Ultimately schools have instilled in all of us a shared baseline of behavior, supported by foundational facts necessary to find consensus.

Today, technology and social media have endangered our ability to reach common ground. The distracting noise of extremists, splintering, and Balkanizing our nation threatens American institutions. Elections, government agencies, city and state government, and yes, schools are all targeted. Navigating through a culturally diverse society is inevitably stormy, and a closed American mind isn’t helpful.

Public education has traditionally been one of the ligaments that bind us all together as one people. Years ago a president encouraged us to ask “what (we) can do for (our) country,” but that’s over. Today it’s “Sorry losers and haters, but my IQ is one of the highest – and you all know it!”

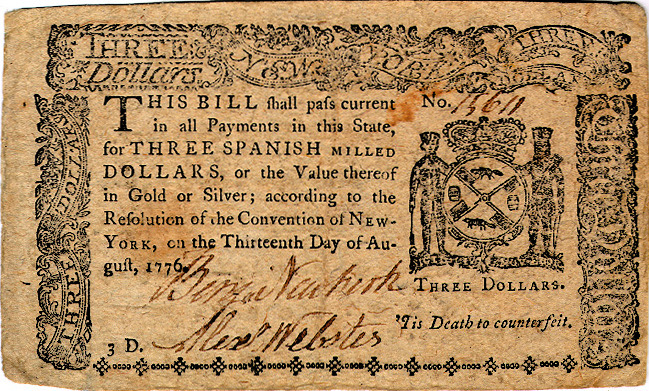

Patriotism and literacy evolved together hand in hand. In 1787 Congress, under the Articles of Confederation, passed an Ordinance for settling western land. This law devised a survey system, to organize states around the Great Lakes region. This is important because sales of one plat of the survey, (you guessed it,) funded public schools.

Thomas Jefferson affirmed the practice by insisting, ”Educate and inform the whole mass of the people… They are the only sure reliance for the preservation of our liberty.”

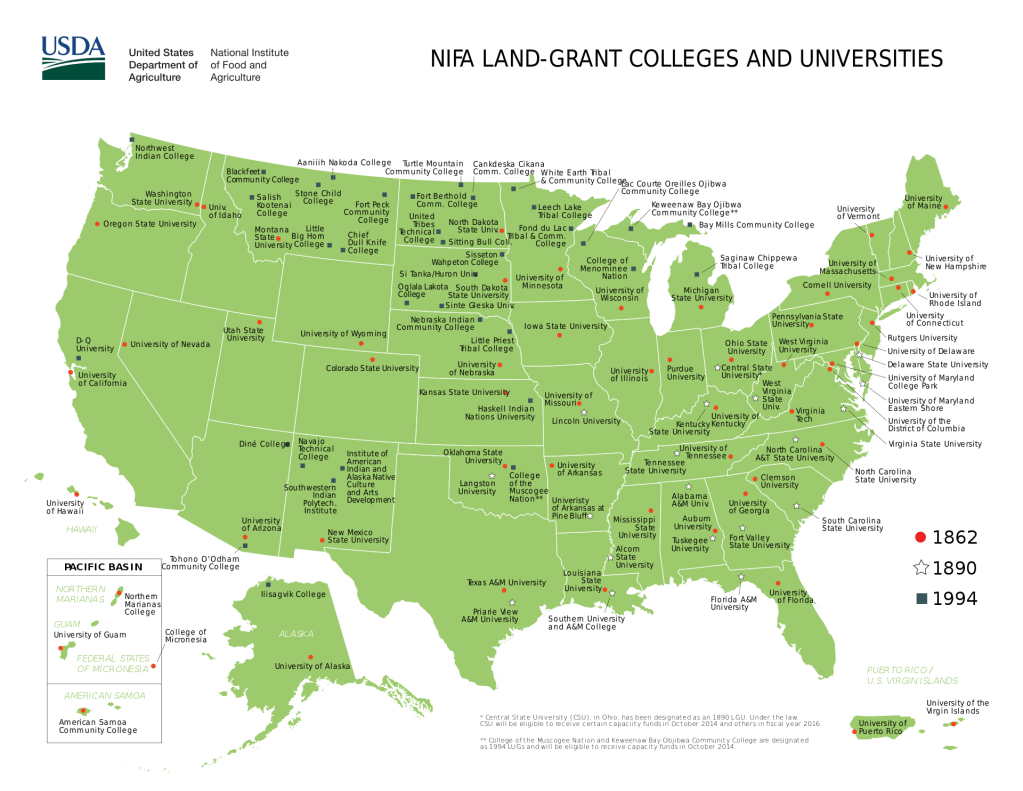

President Lincoln, a figure who deeply lamented his own lack of formal education, pushed to establish land grant universities across the growing nation. The 1862 Morrill Land Grant Act, in particular, financed colleges through Federal funding.These universities today are located in every state of the Union.

America’s erosion of unity is tied directly to the erosion of public education. Our kids are increasingly sequestered into alternative settings; online, magnet, charter, home, and private schools. Missing is the opportunity to experience democracy at its most basic. Students grow familiar with each other, softening our own edges, renewing the energy and optimism of the nation’s promise.

We are all taxpayers, but your local public school isn’t supposed to be Burger King, where every citizen can have it “their way.” We have a system that, regardless of money, race, ability, and social class, all have a seat at the table of democracy.

Gail Chumbley is a history instructor and author. Her two-part memoir, “River of January,” and “River of January: Figure Eight,” are available on Kindle.

gailchumbley@gmail.com