Read River of January for the story behind the pictures.

Gail Chumbley is the author of River of January, a memoir, also available on Kindle. Watch for the sequel, “River of January: Figure Eight” out in November.

Read River of January for the story behind the pictures.

Gail Chumbley is the author of River of January, a memoir, also available on Kindle. Watch for the sequel, “River of January: Figure Eight” out in November.

Eighty-three years ago.

Glendale, California

Glendale, California

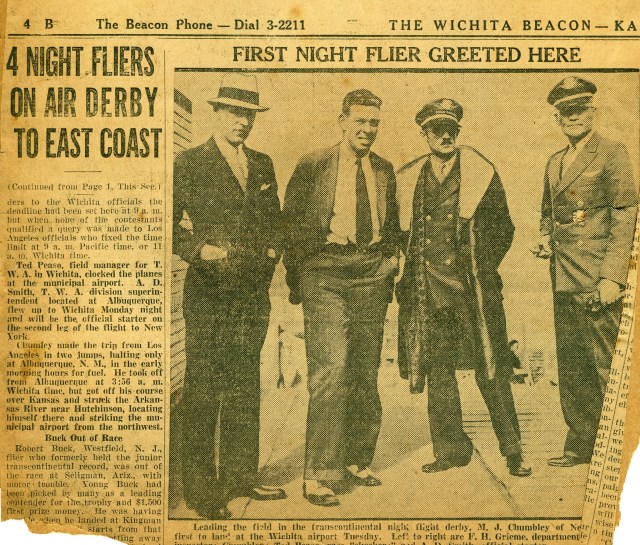

Wichita

Wichita

New York

New York

Gail Chumbley is the author of River of January, a memoir. Also available on Kindle.

Watch for River of January: Figure Eight in November.

A visitor with the “Darkness Derby” trophy

Reno is situated in a golden bowl below mountains that separate Nevada from California. This enormous basin pulsates with life; upscale strip malls, flashy casinos, and relentless traffic following endless suburban growth.

To the north, off the beltway circling the “Biggest Little City,” sits Stead, Nevada, a locale clearly not touched by the same affluence as the rest of the region. A boarded up Catholic church, a Title-I elementary school and a Job Corps Center secured behind a grim, chain link fence, indicate that the very poor live world’s away from the prosperous south.

But at the end of this impoverished section of road, the world changes. Parachutists drift overhead in swatches of white, zigzagging through a deep blue autumn sky. Aircraft of every model and engine size wait, tied down on the asphalt, wing to wing. Vintage bi-planes, silvery jets, oddly shaped experimental aircraft, and muscly aerobatic planes flash in the brilliant sunlight. Thrilled attendees weave through the rows, admiring and discussing these miracles of flight. The owners relax inside the shade of hangars–a protective eye on their aircraft, monitoring visitors with a mixture of casual diligence and satisfied pride.

We, my husband and I, watch the action from inside a tented gift shop in the pits. How the gods of fortune placed us among the elite of the Reno Air Races, in the pits, is a miracle of another kind. In waves, the chosen, carrying pit passes, ebb and flow from our tent. When the Blue Angels blast down the runway, rising in a series deafening concussions, the tent empties. As the spectacle comes to a roaring close, and these seraphs return to earth, the shop once again fills with customers.

These pilots can’t seem to keep themselves from staring at our table. The oversized trophy Chum won in 1933, placed at the center of our book display, captivates these Twenty-first Century flyers. “Can I get a picture of this?” one man asks. “How much would you take for the trophy?” asks another. “They don’t make them like this anymore,” says another. “You need to take care of this one.”

Conversations soon turn to the race itself, 1933’s “Darkness Derby.” For this Depression-era contest pilots flew, one by one, into the eastern twilight. Beginning in Glendale California, nearly twenty intrepid aviators ascended, stopping first in Albuquerque, then north to Wichita, then sprinting to the finish at Roosevelt Field, Long Island. This event celebrated both “Roosevelt Field Days,” and a new Helen Hayes, Clark Gable film titled, “Night Flight.”

Beside the tarnished trophy, we display a framed glossy of Miss Hayes presenting Derby winner, Mont Chumbley, with the very same trophy, at her movie’s premier.

Reactions varied. One pilot gushed that my father-in-law was a bonafide aviation pioneer. Enthused the admirer added, that your father-in-law managed to find his way through the blackness and win the race was incredible–he had no flight instruments. I smile because I already know, and this visitor’s wonder matches my own. I also smile because for the first time, since publishing “River of January,” I’m with people who understand the profound significance of his victory.

Another visitor tells us he edits an aviation magazine out of Ohio, and would like me to submit a piece regarding the “Darkness Derby.” This editor promises us that he will see to it that the race is officially recorded for posterity. My husband and I are very pleased with this assurance, as well. We’d always hoped to get Chum’s accomplishment recognized by fellow aviators and officially recorded.

Happily, Chum isn’t the only recipient of accolades. Equal attention and interest are directed to Chum’s future wife, a lovely girl also named Helen, Helen Thompson. Her photograph lights up our table with timeless beauty and glamor. She smiles from a vintage, Hollywood glossy emitting a radiance that seems to add to Chum’s luster. I quickly add that this girl’s glamor masked her own courage and ambition in the world of entertainment. Helen Thompson too, took enormous professional risks, performing across three continents during the tumult of the early 1930’s. It was in Rio de Janeiro, in 1936, while dancing at the Copacabana Casino, she met her dashing aviator.

In Reno my husband and I stepped into the world of avid flyers, and they understood our purpose in sharing “River of January.” With all the adulation paid to our exhibit, all the books we sold and signed, Chum and Helen’s story is carried on to inspire future generations of adventurers.

Gail Chumbley is the author of the memoir, River of January and River of January: Figure Eight. Book one is available on Kindle.

I cannot recall the words I used to soothe my juniors on that horrible day. However, the soul-deep pain remains remarkably sharp in my emotional memory.

Vaguely I can see my son, a senior at the same high school, enter my classroom to check on his mom, the American History teacher. Seeing his face, I wanted to go to pieces.

It was later, in the local newspaper, that I discovered not only the words I shared with my students but the transforming pain they endured watching their country attacked.

(For the writer’s privacy I’ve deleted their identity)

Gail Chumbley is the author of the two-part memoir, “River of January,” and “River of January: Figure Eight,” both available on Kindle. Chumbley has also composed two history plays: Clay on the life of Henry Clay and Wolf By The Ears a study in racism.

gailchumbley@gmail.com

The fix was in during America’s late 19th Century. This era, remembered as the Industrial/Gilded Age, witnessed awed politicians who regularly legislated and protected those known as robber barons.

Ferocious drama played out for decades following the Civil War. In this fraught atmosphere courageous and determined union organizers risked all to seek economic justice in the face of dangerous obstacles. Unionizers faced their names appearing on a black list, (meaning no one would hire them), bodily harm, and government sanctioned violence. The historic record is littered with instances of brutality, hazardous working conditions, and bloodshed meted out by powerful business owners.

Particularly lethal for workers was attempting to organize workers in American mines, mills, and factories. It didn’t help that the general public was unsympathetic to workers plight, universally convinced by “The Gospel of Wealth,” a secular-sacred creed that maintained the rich were chosen by God, therefore entitled to lord over the working class. In general laborers, especially the foreign-born were viewed as a cheap commodity, a disposable cog in the wheel of production and profits.

Andrew Carnegie, in particular detested the working class, and even more the activists who threatened his control over Carnegie Steel. For example, as a remedy to thwart unionizers, managers deliberately placed workers of different nationalities next to one another on the production line. Language barriers effectively frustrated organizers trying to increase membership. Then there were corporate spies, and hired guns such as the Pinkerton Detectives out of Chicago, or Federal troops sent by Washington to quell strikes. If those measures failed to break the union, Carnegie opted to lock out strikers, filling jobs with scab labor.

The use of an injunction proved a particularly nasty device owners used. A state governor would claim interference of interstate commerce; meaning troops could move in to ensure the free transfer of mail and freight. Once the injunction was issued soldiers were deployed, guns blazing into crowds of strikers, not unlike battles from the recent Civil War.

The most significant use of the injunction concerned the Pullman Strike of 1894. Workers at the Pullman Palace Car Company (think Wild Wild West railcar) sold their freedom to the company’s powerful owner, George Pullman. Laborers lived in his company town, (Pullman, Illinois) where their wages were docked for utilities, rent, and other fees each month. During the economic downturn of the Panic of 1893, hourly wages were drastically cut, but Mr. Pullman still deducted his same monthly payments.

Demanding leniency the Pullman workers voted to strike.

Union leaders knew they had to avoid a federal injunction for armed troopers would intervene leading to violence. Seeking to avoid a military showdown strikers took extra care that the trains continued to roll through Illinois. In solidarity, rail workers helped by unhooking Pullman Cars, parking them on side tracks, then reconnecting the rest of the train cars. Off they chugged to adjacent states.

Mr. Pullman was not amused.

Of course the U.S. Attorney General at the time issued an injunction, ordering federal troops into the fray. Soldiers poured out of rail cars in Pullman, opened fire, killing some thirty strikers, and wounding many more. The strike was broken, but the heavy-handed tactics used by Pullman left some uneasy.

Not that he cared.

Could a land that aspired to liberty, also check the tyranny of powerful industrialists?

Other disputes followed the same pattern; The Haymarket Riot, the Homestead Strike, the Ludlow Massacre in Colorado, and New York City’s tragic Triangle Shirtwaist Fire in 1911 which killed nearly 150 immigrant girls.

Still, despite many violent setbacks, changes began to come about for the working class. When Theodore Roosevelt became president in 1901, he championed some real reforms. In 1902 when a coal strike threatened the coming winter supplies, TR stepped in.

Initially the mine owners refused to recognize the authority of the United Mine Workers and refused to budge.

With winter coming the President took drastic action. Roosevelt essentially sided with the strikers. He threatened the owners, warning he was willing to send in the army, but this time to work coal fields. In short the owners were obliged to sit down with union leaders and negotiate.

This President was not blind to the threat of social and economic injustice.

Fast forward to 1950’s where I grew up in a blue collar, union household. My dad, an active member of the United Steel Workers, tended white-hot pots of molten metal for Kaiser Aluminum. Because of his job, benefits, and union activities, his only daughter (me) earned a university degree, and pursued a fulfilling, professional calling in public education.

Because of the time and the place, my dad’s employment offered benefits neither my mother nor grandmother enjoyed. College, a degree in American History, and a professional career as a teacher. His union job made my professional path possible.

Of course at the time, I didn’t fully appreciate the price paid for my good life, but that four-year degree opened my eyes. The benefits that shaped my path did not come easily.

Today unions are still vilified by many. Nonetheless those who suffered and sacrificed built an American economy that still provides a good living for many . Those valiant few must be remembered.

BTW, industrial workers demanded and won the right to honor the Sabbath as a day of worship, not labor. Those of the Jewish faith and Christian established the tradition of weekends, setting aside Saturday and Sunday.

Have a thoughtful Labor Day

I grew up in a union household. And truth be told, the benefits of the Steel Workers Union saw me through college, making my career in education possible. Through a combination of post-war prosperity, cheap hydro power from the Columbia River, and full industrial production at Kaiser Aluminum, my life took an affirming and enriching path. Of course at the time, I didn’t understand the real cost paid for my good life, until I taught Labor History to high school juniors. What I found in my research was a story of real people enduring violence and intimidation that, in the end, made possible the emergence of America as the world’s greatest economic power.

Labor strikes in the 19th Century were especially bitter, bathed in violence and bloodshed. Operating under the creed of “The Gospel of Wealth,” entitled industrialists viewed workers as a cheap and plentiful commodity, no more than a…

View original post 659 more words