I Want My GOP

https://chumbleg.blog/2018/04/13/i-want-my-gop-3/

— Read on chumbleg.blog/2018/04/13/i-want-my-gop-3/

Worth a reread.

I Want My GOP

https://chumbleg.blog/2018/04/13/i-want-my-gop-3/

— Read on chumbleg.blog/2018/04/13/i-want-my-gop-3/

Worth a reread.

“It’s hard to remember that they were men before they were legends, and children before they were men..” Bill Moyers, A Walk Through the Twentieth Century.

For Presidents Day I’ve been putting together a lecture series for my local library. These talks surround the childhoods and later experiences of George Washington, Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt.

The thinking behind the series was that early life for all four men presented serious challenges. Complications in health, family tragedies, and economic circumstances appear to have shaped the temperaments and the world view of these future presidents.

It was how each overcame difficulties and setbacks, and how that endurance came to influence each of their presidencies.

This is a brief synopsis of what I found.

Behind the image mythologized in “The Life of George Washington, by writer, “Parson” Weems, obscures the reality of a more nuanced, and complex Virginia child. Born on February 22, 1732 in Pope’s Creek, George Washington came into the world as the first son of a planter, but from a second marriage. His position in the family line left him without any claim to his father’s estate, or assured public standing. In Tidewater Virginia, society strictly followed the rules of primogeniture, where only the eldest male inherited, and young Washington could claim nothing, aside from the family name. His father, Augustine Washington had two sons from a first marriage, and Lawrence, the eldest, stood to inherit all.

Augustine in fact died in 1743, when George was only eleven years old, the boy not only lost his father, but also lost the formal English education his older brothers had enjoyed. That particular shortcoming forever marked George, leaving him self conscious and guarded through his early life.

To find his way, the youth conducted himself with quiet poise; it was a conscience effort designed to enter the upper echelons of society. Over time, with constant practice, Washington successfully hid his insecurities behind a restrained, and formal persona. So proficient at playing the gentleman, Washington, in fact, became one.

The Revolutionary War that Washington later tenaciously served, cost young Andrew Jackson his family. Born on the frontier, in a region paralleling North and South Carolina, young Andrew arrived into the world without his father. Jackson Sr had died months before, leaving Andrew’s mother, Elizabeth, and his two older brothers destitute.

At thirteen Andrew, along with his brother Robert, joined the Patriot ranks as runners, only to be captured and imprisoned by the Redcoats. While a captive an officer of the Crown ordered young Andrew to polish his boots, and the boy refused. Young Jackson claimed he was a “prisoner of war, and demanded to be treated as such.” The officer replied by whipping his sword across Jackson’s insolent head and forearms, creating a lifelong Anglophobe. (In January, 1815, 48-year old Colonel Andrew Jackson meted out his revenge on the Brits at the Battle of New Orleans).

The end of the Revolution found young Andrew alone-the only survivor of his Scots-Irish family. His brother Robert had succumbed to camp fever from his time as prisoner, followed by his mother three weeks later. For the rest of his long life, Andrew Jackson lashed out, perceiving any criticism as a challenge to his honor and authority. He governed with the desperate instincts of a survivor.

Of a mild, more genial temperament, Abraham Lincoln came to being in the wilds of Sinking Springs, Kentucky, near the settlement of Hodgenville. His father, Thomas Lincoln, was a hard scrabbling farmer, while his loving mother Nancy Hanks lived only until Abe reached the age of nine. Hard work, deprivation and tragic personal losses seemed to permeate Lincoln’s young life, and as he grew Abraham grappled with serious bouts of melancholy.

Exhibiting a quick and curious mind, he struggled to educate himself on the frontier. Largely self-taught, Lincoln grasped the rudiments of reading and spelling, but his father saw schooling as idling away time better suited to work. Young Lincoln had to find tricks to do both, such as clearing trees then reading the primer he kept handy.

His step-mother, Sarah Bush Johnston reported that Abe would cipher numbers on a board in char, then scrape away the equation with a knife to solve another.

By young adulthood Lincoln left his father’s farm, and relocated to central Illinois, and made a life in the village of New Salem. Over time, Lincoln grew remarkably self-educated, studied law and passed the Illinois bar in 1836.

Of all the resentments he felt toward his father, it was Thomas’s clear lack of ambition and self improvement that nettled the son most. Upward mobility was America’s greatest gift, and young Lincoln pursued it with relish.

From his first gasping moments Theodore Roosevelt struggled simply to breathe. A child of rank, privilege and wealth, he suffered from debilitating, acute asthma. His parents, Theodore Sr and Mitty Bullock Roosevelt, stood helplessly over his sick bed, fearing that their little boy wouldn’t survive childhood. Later TR recalled how his father would lift him from his bed, bundle him into an open carriage for a long ride through the moist Manhattan night. Small for his age, and nearly blind, young Teedee as he was called, began an exercise regime in a gym, built by his father on the second floor of their palatial home on East 20th Street in New York. Over time, using a pommel horse, the rings, and a boxing speed bag, Theodore Jr visibly grew.

As for his eyes, a hunting trip finally proved to his family that he just couldn’t see. With new glasses, a self made physique and a dogged determination, Theodore Roosevelt brought his indefatigable zest and energy into his presidency.

Today is Presidents Day, 2018, and there is great value in remembering those who have served in this experiment in democracy. All four of these presidents left a distinctive signature of governance, schooled by earlier experience. And all, even Andy Jackson, governed in the spirit of service, believing they could make a contribution to this boisterous, ever-evolving experiment called America.

Gail Chumbley is the author of the two-part memoir, “River of January,” and “River of January: Figure Eight.” Available on Kindle.

gailchumbley@gmail.com

Each school year, by spring break, my history classes had completed their study of the Kennedy years, 1961-1963. We discussed the glamor, the space program, civil rights, his charisma and humor with the press, and most importantly, JFK’s intense struggle with Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev.

In a provocative challenge to America, Khrushchev had ordered the building of the Berlin Wall, and construction of nuclear missile sites in Cuba. This second and more dangerous challenge prompted the 1962 Missile Crisis.

We probed further into the delicate diplomacy that, after 13 days settled that perilous moment peacefully.

For years I closed the unit joking, “aren’t you glad Andrew Jackson wasn’t president?” That line always drew a good laugh.

But really high stakes foreign crises is no longer funny. Not in today’s political climate.

America’s seventh president was a mercurial character. He loved blindly and hated passionately. If convinced his honor had been besmirched, the man dueled—sometimes with pistols, sometimes with knives. It all depended upon his mood.

The provocation behind most of these confrontations touched upon Jackson’s wife, Rachel, who had a complicated past.

A murderer, the author of the Trail of Tears, a plantation and slave holder–Jackson was deadly dangerous.

No financial wizard, he went on to destroy the Second Bank of the United States, the central financial institution of the young country. Old Hickory then deposited the government’s money into pet banks, local private, unregulated concerns across the country. Mismanaged, these banks collapsed, propelling America into one the longest, deepest depressions in American history.

Jackson ignored the Court, and he used the military for his own political gain.

The power King Andrew exercised rivaled the Almighty’s.

So the joke regarding the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 resonated with high school juniors. JFK’s skillful restraint in that perilous moment would certainly have resolved differently in the hands of the hotheaded, autocratic, Andrew Jackson.

Again, the joke is no longer funny.

Now America is saddled with an impulsive autocrat whose hunger for authority tramples our time honored liberties. He is attacking our communities, and arresting neighbors for his political gain. Moreover, this petty Napoleon shows little understanding of America’s legal tradition–basic high school history,, or civics. Then there are the ill-advised tariffs playing hell with the economy. Like Andrew Jackson, this current “president” carries himself as another absolute monarch.

The pertinent question this tale raises is this; what could this current, petty president, with little impulse control do in the turmoil of a similar crisis?

Tonight, June 21, 2025 we now know. This cannot end well.

Gail Chumbley is the author of the two-part memoir, “River of January,” and “River of January: Figure Eight.” Chumbley is also the author of three plays set in American history, and co-authored a screenplay based upon her books.

gailchumbley@gmail.com

President Andrew Jackson has stopped spinning in his grave. Finally. He hated paper money with all the fiber in his being, and now thankfully for him, no longer tacitly endorses its use. Jackson was a sound money man and believed gold the only genuine medium of exchange . . . weigh-able, bite-able gold; good ole “cash on the barrel-head.” In fact, the President believed so passionately in the principle of gold bullion that he banned any use of paper money for any transaction whatsoever. This same policy, in the end, torpedoed the US economy and triggered the Panic of 1837.

That financial disaster held on for over five chilly years.

But the day has arrived, America has finally heard Jackson’s cries of anguish from the great beyond, and removed his likeness from that raggedy heresy of ersatz value. Still, one has to wonder. What would General Jackson make of runaway slave, Harriet Tubman taking his place on legal tender?

Ms. Tubman, as a woman, and as a slave, lived invisibly in Jackson’s world. The only notice a planter like Jackson would have made was Tubman’s incorrigible practice of stealing another master’s property. For a man of deep passions, of violent loves and hates, her offense would have pissed this president off, and sent him into a dangerous rage. In his world of master and slave, her offenses allowed no mercy, no reprieve.

As for Tubman? She understood a truth that Jackson could never, ever have comprehended—that justice was a force that bore no designation to color, gender, or appraised value. A mighty truth reigned far above the limited aspirations of General Andrew Jackson, killer of banks, Natives, and the hopes of the hundreds he held in bondage.

Tubman’s idea of honorable behavior had nothing to do with white men firing pistols on dueling grounds, and that white social conventions which condemned her to servitude were wholesome and noble. The human condition, as Tubman understood the meaning, held a deeper significance, an importance that required a profounder appreciation. The world of plantations, race hatred, whip wielding overseers, and economic injustice held no real sway, and certainly possessed no honor.

Jackson’s opinions truly hued in only black and white, and that outlook wasn’t limited to skin color. Abstract ideas like ‘humanity’ didn’t resonate in his mind, too ethereal for a man who loved gold coins. Banks were bad, women were ornaments, Indians were fair game, and blacks were slaves. That simple. Of course at the same time, this limited world view gave a figure with Tubman’s vision the edge. If a man of Jackson’s time and station caught a glimpse inside the real thoughts of his “family” members living over in the slave quarters, his mind would have been blown.

So it is with some satisfaction that Harriet Tubman replaces Andrew Jackson on the twenty-dollar bill. But not only because she’s a woman, nor only because she’s black. The star she followed may have literally sparkled in the northern sky, but every footstep she trod signified progress on the road to realizing the immeasurable value in us all.

Gail Chumbley is the author of the memoir River of January

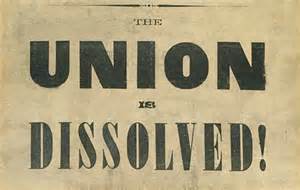

A divided national party . . . voices of extreme rhetoric . . . an ugly, contentious primary season. Does this spell doom for two-party system?

Sounds modern, doesn’t it? But the year was 1860, and the party in question was founded by Thomas Jefferson, and shaped in the image of Andrew Jackson: The antebellum Democratic Party.

On the eve of Civil War, the future of the Union appeared in fatal doubt. Political leaders in the Deep South: South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Florida had all but washed their hands of the centrally powerful United States. Adding to the precarious atmosphere, a faction of Democrats in the North promoted a policy to permit slavery into the western territories under the principle of Popular Sovereignty, or direct vote. Others voices in the northern branch of the Democratic Party believed the Southern States should depart the Union in peace. And these pro-secession advocates became the most worrisome threat for Senate leader, Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, the leading Democratic candidate for the presidency in 1860.

Douglas found himself in a hell of a spot. He fervently burned to lead his party to the White House and save his nation, dangerously poised on the verge of civil war. As the principal heir to Senate leadership, Douglas had spent over twenty years in Congress working to stave off Southern secession, taking over when Kentucky Senator, Henry Clay, the “Great Compromiser” died. Clay had also spent most of his earlier career drawing up one concession after another in a noble attempt to preserve the nation. Eventually the effort wore him out, and Senator Douglas pick up the cause.

As far as Douglas was concerned, slavery wasn’t a moral issue, but a bump in the road. The issue could easily be decided by the good folks migrating west. Douglas believed if settlers didn’t want slavery, they would decline to establish laws necessary for supporting the “peculiar institution.” He was wrong—dead wrong. Slavery had, by 1860 become an issue impossible to solve. And it was here, underestimating the power of the slave issue, that the Illinois Senator imploded his party and his career.

The new Republican Party had formed six years earlier in Wisconsin, established on one central principle—slavery would not extend into the western territories, period. And this new party grew fast. Composed of splinter groups, this now fully unified party maintained that free labor was an integral component of free market capitalism. The presence of slavery in growing regions of the West would devalue free labor, and undermine future economic growth.

Now, don’t get me wrong, these Republicans did not sing Kumbaya or braid their hair. These men did not believe in equality between the races—they were not abolitionists. Economic principles drove their political platform, (Emancipation came later with the transformation of President Lincoln in the fire of war).

For Stephen Douglas the approaching 1860 election meant vindication for his support of popular sovereignty, and reward for his faithful political service. And Douglas was no political hack. He fully understood the solvency of the Union lay in the delicate art of sectional balance, and his ascendancy to the White House as a Democrat would go a long way to placate the Southern hotheads. But this Illinois Senator failed, once again, to fully comprehend the temper of the nation, or of his own party. The era of seeking middle ground had passed—America’s course had been set toward industrial modernity with no place for an antiquated, barbaric labor system.

Charleston, South Carolina, was selected as the site of the 1860 Democratic convention. Chaos immediately broke loose on the convention floor. While Southern Democrats demanded strict, exact language guaranteeing the extension of slavery in the territories, Northern Democrats and those from California and Oregon pushed for Douglas’ popular sovereignty. This tense deadlock forced the latter faction to walk out and reconvene in Baltimore where party business could move forward.

Southern Democrats moved on as well. In a separate Richmond, Virginia convention Southern Democrats nominated Kentuckian John C. Breckinridge.

In Baltimore, Douglas indeed gained the Democratic nomination, preserving his precious principle of local elections determining the western expansion of slavery. Bolting Democrats in Richmond went further adding an absolute protection of slavery to their platform. Middle ground vanished.

Though a long shot, a third faction of the Democratic Party broke ranks calling themselves the “Constitutional Union Party.” I’m not sure what they stood for, but clearly it wasn’t support for Douglas or Breckinridge. Convening in Baltimore as well, in May of 1860, this coalition nominated John Bell of Tennessee.

So what can we make of this 1860 fiasco today, in 2016? If I could attempt a bit of divination I would suggest that the political party that can present the most united front will prevail in the general election. If current Republican candidates continue to employ such wide-ranging, and scorching tones to their rhetoric, and stubbornly defend the innocence of their loose talk, the party may run head long into oblivion, as did the Democrats of 1860. If the roaring factions, so loudly represented by each GOP aspirant goes too far, the fabric of unity will shred, crippling the Republican’s ability to field serious candidates in the future.

Looking at the past as prelude much is at stake for the unity of the GOP. In 1860 party divisions nearly destroyed the Democratic Party, and launched the nation into a bloody civil war. And though Republicans at that time elected our greatest Chief Executive, Abraham Lincoln, the Democrats suffered for decades, marginalized as the party of rebellion. And even the best lessons left by the past are still forgotten in the heat of passion by those who know better. The Democrats shattered their party unity once again a hundred years later, splintered by the Vietnam War, social unrest, and racial strife. This is truly a cautionary tale for today’s splintering Republican Party.

Zealots do not compromise, and leading GOP candidates are spouting some pretty divisive vitriol. Southern Democrats self righteously rejected the national party certain it no longer represented them, and ultimately silenced the party of Jefferson and Jackson for decades. The lesson is clear for today’s Republicans. By tolerating demagoguery, extremism, and reckless fear-mongering in their field of contenders, the RNC may indeed face a similar demise. Now its true that no party can be all things to all citizens, nor should hardened splinter groups run away with the party.

The American public demands measured and thoughtful candidates—and both parties are expected to provide candidates of merit and substance.

We deserve leaders worth following.

As Senator Stephen Douglas refused to recognize that the political skies were falling around him, and his party, the modern Republican Party must not.

Gail Chumbley is the author of River of January, a memoir. Available on Kindle

My mother has made it quite clear that she wants to live at home until the very end. Any member of our family daring to even think ‘assisted living’ can expect a reaming on the scale of a super nova. Mom has no reason to transplant elsewhere. She has her recliner, her adjustable mattress, her crossword puzzles, and her memories in that house. After 53 years under the same roof there is no other place–that home is the center of her universe.

Oddly enough her story somehow broaches the subject of why people do move—in this instance, the story of immigration to America.

The 19th Century American humor magazine, Puck once declared that “Princes’ don’t immigrate,” and that truth has found a lot of support in our historic record. Just a glimpse of current film footage along southern European borders powerfully demonstrate this 19th century truism. The vulnerable from Syria and other destabilized regions of the Middle East grapple with hate, fear and barbed wire to carry their families to safety.

Immigrants to American shores have all shared similar reasons to exchange the familiar, for the unknown. A brief look at America’s earliest settlers well illustrates this dynamic from 1620 to the present.

Some folks were pushed, some were pulled, but all European newcomers set foot on Atlantic shores because there was no reason to remain in the familiar.

Challenges to the Catholic Church provided the first steps toward the flow of populations to leave Great Britain. The Protestant Reformation essentially secularized the English Church, rejecting and replacing the Pope for the British sovereign as leader. Devout believers felt that King Henry’s English Reformation did not go far enough in ridding sacraments for deeper Biblical understanding. This faction became known as “Puritans,” those who wished to cleanse the English Church of all vestiges of Catholicism.

The religious struggle in the British Isles was long and complicated, but ultimately resulted in systematic Puritan persecution. Two phases of believers departed Great Britain as a consequence. First, were the Separatists led by William Bradford, who believed England was damned beyond redemption. This group settled first in Holland, then acquired funding for a journey on the Mayflower to Massachusetts Bay. Americans remember these folks as the Pilgrims.

Almost ten years later another group of mistreated reformers made landfall further north, closer to Boston. This wave of settlers, unlike the small trickle in Plymouth, came to Massachusetts Bay in a metaphoric deluge. Thousands upon thousands of Puritans departed England, driven out by an intolerant, albeit re-Catholicized crown. Called the Great Puritan Migration, refugees from religious bullying settled from Cape Cod, to the Caribbean.

The Quakers, or Society of Friends, made up another group pushed out of England. In a stratified culture of forced deference to one’s “betters,” this faith recognized the innate equality in all people. Quakers, for example, refused to swear oaths or ‘doft’ their hats in the presence of “gentlemen,” and that impudence made the sect an intolerable challenge to the status quo.

William Penn (Jr.) became a believer in Ireland, and found this punitive treatment of Quakers unjust. However, as a wall to wall adherent to peace and brotherhood, Penn used his childhood connections to the aristocracy to depart to America. King Charles II granted Penn a large tract of land in the New World, where Penn and his followers settled in the 1660’s. “Penn’s Woods,” or Pennsylvania set up shop establishing the settlement upon the egalitarian principles of Quakerism.

The father of President Andrew Jackson, Jackson Senior, stands as an excellent example representing another wave of humanity dispensable to the British Crown. Dubbed Scots-Irish, these were Scotsmen who resisted British hegemony and unification for . . ., for . . ., well forever. (Think of Mel Gibson in Braveheart.) First taking refuge in Ireland, this collection of rugged survivors, by the 1700’s, made their way to America. Not the most sociable bunch, these refugees found their path inland, eventually settling along the length of the Appalachian Mountains. Tough and single minded this group transitioned from exiles to backcountry folk.

Now the settlers in Jamestown and Georgia offer a different explanation for permanent human migration.

The London Company of Virginia, a corporation, funded an expedition to Jamestown in 1607. Soldier of Fortune, Captain John Smith and his compatriots crossed the Atlantic to get rich. Inspired by the example of Spanish finds in Mexico, these English mercenaries were hopeful of finding golden cities of their own. Almost a disastrous failure, the Jamestown colony survived, not by precious metals, but from cultivating a Native crop . . . tobacco. Eventually arrivals outnumbered departures in the stabilizing Virginia settlement, and the addictive crop paid handsome dividends for London investors.

Georgia, the most southern colony came last, founded in 1732. The brain child of social reformer, James Oglethorpe, this colony of red clay became a dumping ground for victims of England’s byzantine criminal codes. Those of the lowest rungs of English society, from petty pickpockets to hardened felons found themselves “transported” to Oglethorpe’s colony for second chances, and out of the hair of English jailers.

On a side note, slavery explicitly was forbidden in the Georgia charter. And that raises the issue of the last group forced to American shores; African slaves. These unfortunate souls did not want to leave their homes in West Africa. Much like my mother, this group did not wish a new life in a new land. Economic demands brought about this “Middle Passage,” the despicable trade in human cargo, kidnapped for the New World. Force, brutality, and exploitation wrenched these people from their lands to serve those who for contrasting reasons came to live in America. The injustice of this “African Diaspora” still plagues an American society grappling to resolve this age-old injustice.

Caution ought to guide current politicians eager to vilify and frame immigration as an inherent evil and subverting occurrence. No one lightly pulls up roots. Leaving all that is familiar is an act of desperation, a painful and difficult human drama.

Americans today view our 17th Century forebears as larger than life heroes, but their oppressors saw these same people as vermin–as dispensable troublemakers who threatened good social order. This human condition remains timeless, and loose talking politicians and opportunists must bear in mind the story of the nation they wish to lead.

Oh, and my 84-year old mother just remodeled the house, keeping her Eden fresh and new.

Gail Chumbley is the author of River of January, and the newly published River of January: Figure Eight.