Right now, in classrooms across America, and overseas, thousands 17-year-olds are preparing for the AP US History exam. They, and their instructors are obsessed with cause and effect, analyzing, and determining the impact of events on the course of America’s story. Moreover, they are crazed beyond their usual teen-angst, buried deep in prep books, on-line quizzes, and flashcards. As a recovering AP teacher, myself, I can admit that I was as nuts as my students, my thin lank hair shot upward from constant fussing.

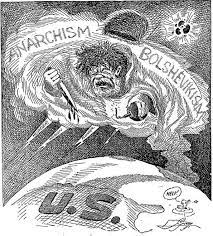

My hair fell out too, embedding in combs and brushes, as I speculated on essay prompts, that one ringer multiple choice question, and wracking my brains for review strategies. The only significance the month of April held was driving intensity, drilling kids on historic dates; Lexington and Concord, the firing on Fort Sumter, the surrender at Appomattox Courthouse, President Wilson’s Declaration of War in 1917, the battle of Okinawa, MLK’s murder, and the Oklahoma City bombing, That was what April meant in April.

To quote John Lennon, “and now my life has changed, in oh so many ways.” Today April holds a whole new definition. My husband rises first in the morning, putters in the kitchen, fetches coffee, tends to the dog, and is back in bed, back to sleep. Big plans for my morning include writing this blog, making some calls related to book talks, a three mile walk through the Idaho mountains, then working on Figure Eight, the second installment of River of January. What a difference! Nowadays, getting manic and crazy is optional. My hair has grown back in, standing up only in the morning, and the only brush with AP US History occurs in my dreams; the responsibility passed on into other capable hands.

This month, at least here in the high country, has been especially beautiful. We have already enjoyed a few 70 plus degree days, and the green is returning to the flora. Our sweet deer neighbors are no longer a mangy grey, emerging from the trees wearing a warm honey coat. With a little snow still on the peaks, the sky an ultra blue, and the pines deep green and rugged, I think sometimes this must be Eden.

My years as a possessed, percolating history instructor provided a gift of passionate purpose that enriched me more than depleted. But, now . . . I wouldn’t trade this new phase of my life for all the historic dates in April.

Gail Chumbley is the author of River of January also available on Kindle.