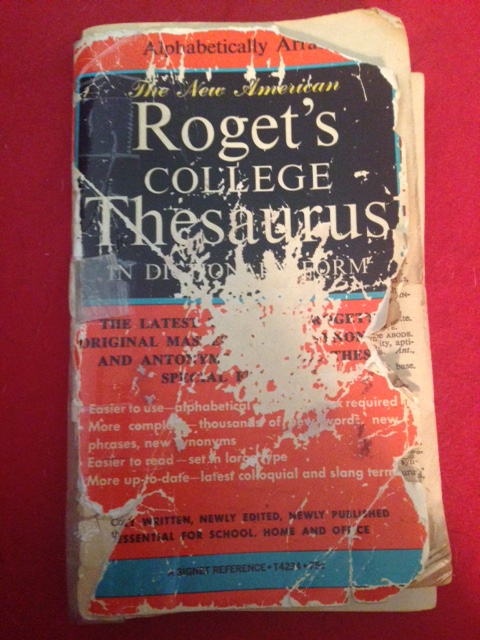

My secret weapon.

Gail Chumbley is the author of River of January, a memoir. Also available on Kindle

My secret weapon.

Gail Chumbley is the author of River of January, a memoir. Also available on Kindle

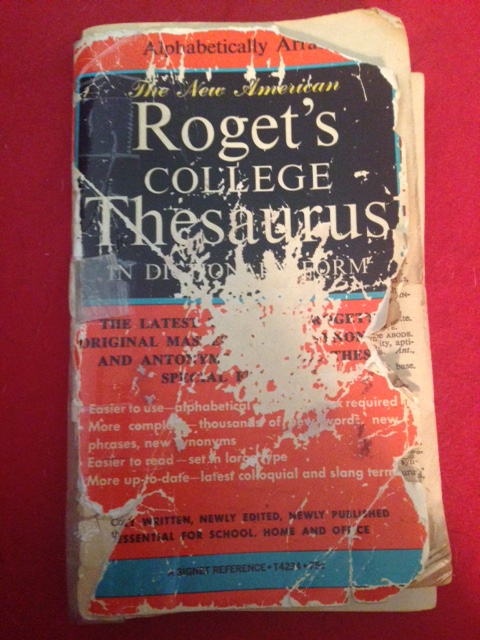

April 14, 1865 fell on Good Friday. It had been five days since General Lee’s surrender to General Grant at Appomattox Courthouse, and a good, Good Friday for President Lincoln. In high spirits, the President escorted his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln to Ford’s Theater for the final curtain of the comedy, “Our American Cousin,” starring Laura Keene. From his seat in the presidential viewing box, Lincoln was murdered at point blank range by an assassin sneaking from behind.

This famous scenario provides quite the ironic twist considering the high opinion Lincoln held for actors and plays. In a cruel irony, President Lincoln sought refuge from his storm of troubles in Washington theaters, a setting where he could lay down his burdens.

From his earliest days in the White House, Lincoln avidly sought out the Capitol’s many stages. An enthusiast, he fell into the dangerous habit of sneaking out of the mansion, without his wife, without any protection detail, determined to take in any new production advertised in Washington papers. Members in various audiences, who spied the President playing hooky, reported that Lincoln watched these plays transfixed, as absorbed as if he was alone rather than seated in a crowd. Apparently his determination in attending Washington City theaters seemed to eclipse even concern for his own safety and in a city ripe with rebel sympathizers looking to inflict harm on the President.

What could impel a Chief Executive to take such risks in wartime, when many wished him ill? Why would Lincoln place himself in such peril?

Neither a drinking man, nor much interested in other vices, the President instead relished stories, either written or dramatized, where he found the distraction and solace he so desperately needed. A prolific story-teller himself, Lincoln appreciated a well turned tale, either in the books he voraciously consumed, or the yarns regaled on a late night near a warm wood stove. This president hungered for diversions to ease his troubled mind weighted by his intractable problems.

And Lincoln’s burdens, both personal and those of the presidency reached far beyond terrible. A protracted and bloody Civil War, the pain-in-the-neck generals who consistently failed in their duty, his difficult wife, Mary, the tragic loss of two young sons, and an unending flow of reverses from irascible members of Congress. That a well-crafted drama or comedy seemed to salve Mr. Lincoln’s soul must have made the temptation of escaping the White House irresistible, and a nightmare for those Pennsylvania troopers assigned to protect him.

Wilkes Booth knew Lincoln would attend the closing night at Ford’s Theater. The owner of Ford’s Theater had advertised that fact earlier in the day. Booth had, in fact, visited the site to prepare for his ‘greatest’ performance. The narrative in the actor’s deranged thoughts, screamed vengeance and duty to the lost cause of the Confederacy.

But I would like to offer another perspective on those same last moments in President Lincoln’s life.

The narrative Lincoln likely played touched more upon hope and delight. Slavery that April night, existed no more in America, and the battlefields had grown quiet. Much work lay ahead for the nation, but Lincoln knew he would attend to those matters as they emerged. For that one night the President did what he loved most—attended a theatrical production, and even better for his rising spirits, a comedy.

At the moment Booth pulled that derringer’s trigger, Lincoln was laughing. The whole audience, in fact, had erupted in guffaws, at an expertly delivered punch line. Perhaps that is how we ought to frame the horrific murder of our greatest commander in chief. While the murderer fumed in hate and revenge, Lincoln over flowed with concentrated joy, reveling in all that was good.

Gail Chumbley is the author of River of January, also available on Kindle

April 9th, today marks the 151st anniversary of General Lee’s surrender to General Grant at Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia, ending the Civil War.

Lee didn’t want to to do it. He remarked to his aides that he’d rather ride his horse, Traveler, into a meadow and be shot by the Yankees, than surrender. But the General didn’t relinquish his burden that way, instead he did his duty.

Even General Grant sat in awe of his most worthy foe. Poor Grant seemed to have felt his social inferiority even in the midst of his greatest military victory. Grant informed Lee he had seen him once in the Mexican War, almost stalling, avoiding the business at hand. The Ohio-born Grant came from humble beginnings becoming one of the most unlikely warrior-heroes in history. Graciousness and duty impelled the Union Commander to receive General Lee with quiet, somber respect.

I would bet that though all participants ardently desired peace, no one exactly wanted to be in that room on that April 9th. The war had cost too much, more than any nation should have to bear. So many losses, so much blood; the cream of the Confederate command only memories to the bowed Lee. Grant, musing the thousands he ordered into the murderous fire of Rebel cannon and shot. The deadly dance, just ended, between two worthy foes, from the Wilderness, to Cold Harbor, to Yellow Tavern, to Petersburg, and finally to the quiet crossroads of Appomattox, and peace.

These two generals, and the loyal armies they commanded had set aside all personal concerns, steeled themselves and did their duty, in Lee’s words, faithfully.

Gail Chumbley is the author of the memoir, River of January Also available on Kindle.

You’re on vacation! Kick back and read River of January on Kindle!

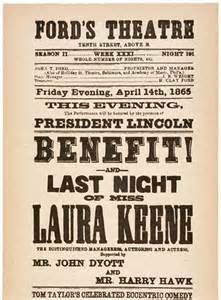

In May, 1940, as British and French troops gathered on the beaches of Dunkirk waiting for a miracle, America remained lulled in complacency. Mont Chumbley, the primary figure in the memoir, “River of January: Figure Eight,” continued his sales flights for Waco Aircraft Company. The war came to the US a year and a half later.

This is Mont Chumbley’s logbook, recorded in early May, 1940. Two fellow pilots appear in this ledger, inscribed nearly 76 years ago. First, HC Lippiatt of Los Angeles, was best known as the largest aircraft distributor on the West Coast. Lippiatt specialized in Waco airplanes, and that fact frequently brought Waco sales representative, Chumbley to Lippiatt’s Bel Air “Ranch.” Another historic figure was Hollywood director, Henry King, best known for films such as “Twelve O’Clock High,” “The Sun Also Rises,” and “Carousel.” Chum explained that he sold King a Waco plane, and in the transaction the two men became fast friends.

For one week in May of 1940, Chum spent time with both airplane enthusiasts.

Henry King (with Tyrone Power & Patsy Kelly) The grand “ranch” of HC Lippiatt

The story behind this logbook entry appears in “River of January, The Figure Eight,” part two of the story, out this summer.

Gail Chumbley is the author of River of January, a memoir. Also available on Kindle. River of January: Figure Eight, part two of the story can be found at www.river-of-january.com

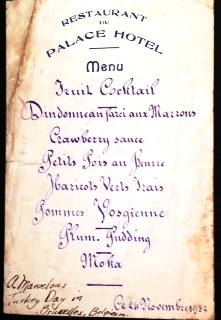

Hand lettered menu from The Palace Hotel in Brussels, Belgium, celebrating an American Thanksgiving, 1932

The dance company all autographed the occasion on the back side.

Note Mistinguett’s signature in the lower left quadrant. Many of these figures appear in River of January

Gail Chumbley is the author of the memoir, River of January, also available on Kindle

Chum’s logbook for September 13, 1933. Note the comment CC for cross country, then the added notation, stunt.

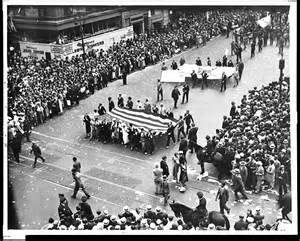

Piloting his Waco C, Chum performed above President Roosevelt’s spectacular National Recovery Act Parade in New York City–the flagship agency of the President’s New Deal.

(Click below for a street level view of the 1933 parade)

Read River of January, a memoir by Gail Chumbley. Also available on Kindle.

New York, 1931

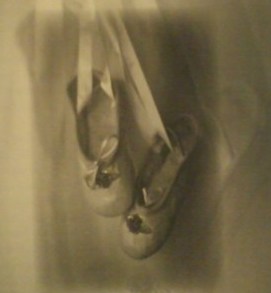

Early for Helen’s Gambarelli audition at the Roxy, the girl and her mother crowded among throngs of other hopefuls. Mothers pulled distracted daughters through the bedlam, while their girls tried to catch words with each other. All the dancers were dressed in rehearsal skirts, tights, and leotards—toe shoes slung over shoulders, or around necks. A pianist, oblivious to the chaos, loudly played echoing chords from the stage. Reaching for her mother’s hand, Helen, shouldered her way to a pair of empty seats to the right of the center aisle.

For the next three hours the two women witnessed extraordinary dancing. Yet while watching her competition perform their hearts out, Helen remained tranquil. She knew her craft—she knew she could compete. She had continued to train with her dance instructor, Mr. Evans regardless of her other obligations.

“Helen Thompson,” a small male assistant, with a receding hairline, read from a clipboard.

Helen rose, glancing at Bertha with a small smile. A little jittery when she stepped onto the stage, the girl’s dedication and discipline overrode her nerves. She posed, arms up, gracefully curved, head back, chin raised to the right, and she struck her regal beginning position. The pianist struck the opening bars, and her talent, training, and passion combined into graceful execution. Helen presented Stravinsky’s Firebird—the tableau in which the Firebird rejoices over the destruction of the evil Kashchei. Her mastery of fluid motion and grace assured Helen’s selection for a spot as a Gambarelli “Beauty,” and she began rehearsals with a new troupe of ballerinas almost immediately after auditions.

Gail Chumbley is the author of the memoir, River of January, also available on Kindle

Happy 134th Birthday to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt who, rather than exploit uncertainty in a time of crisis, reassured Depression-era Americans.

Read River of January by Gail Chumbley, a memoir. Also on Kindle

Still looking for that right gift for that special person on your list?

Order River of January, a historical memoir as a perfect present, today.

Also available on Amazon.com