Harry Truman understood the gravity of his duty right off. When FDR died in April, 1945, the newly installed Vice President got the word he was now president. And what a Herculean task he had before him. A world war to end, conferences abroad, shaping a new post-war world, and grappling with the human rights horrors in both Europe and in the Pacific. Add to all of that, he alone could order use of the newly completed Atomic Bomb.

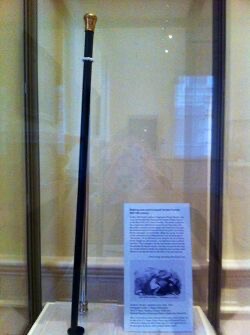

On his White House desk, President Truman placed a sign, “The Buck Stops Here.” With that mission statement Harry Truman stepped up to his responsibilities despite the formidable challenges he faced.

Did Truman inherit the worst set of circumstances of any new president? Maybe? But it is open to debate.

America’s fourth President, James Madison, found himself in one god-awful mess. His predecessor, Thomas Jefferson had tanked the US economy by closing American ports to all English and French trade. Those two powerful rivals had been at war a long time, and made a practice of interfering with America’s neutrality and transatlantic shipping. Despite Jefferson’s actions the issue of seizing US ships and kidnapping sailors never stopped. By 1812 President Madison asked for a declaration of war against England that, in the end accomplished nothing but a burned out White House and defaced Capitol.

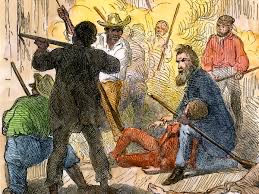

Following the lackluster administrations of Franklin Pierce, then James Buchanan, Abraham Lincoln stepped into a firestorm of crisis. Divisions over the institution of slavery had reached critical mass, and Lincoln’s election was enough for Southern States to cut ties with the North. So hated was Lincoln, that his name did not appear on the ballot below the Mason-Dixon. And the fiery trial of war commenced.

The Election of 1932 became a referendum on Herbert Hoover, and the Republican presidents who had served since 1920. Poor Hoover happened to be in the White House when the economic music stopped, and the economy bottomed out. And that was that for Hoover. His name remained a pejorative until his death.

Franklin Roosevelt prevailed that 1932 election, in fact won in a landslide victory. Somehow Roosevelt maintained his confident smile though he, too, faced one hell of a national disaster.

In his inaugural address the new President reassured the public saying fear was all we had to fear. FDR then ordered a banking “holiday,” coating the dismal reality of bank failures in less menacing terms-a holiday. From his first hundred days the new President directed a bewildered Congress to approve his “New Deal.”

The coming of the Second World War shifted domestic policies to foreign threats as the world fell into autocratic disarray. FDR shifted his attention to the coming war. When President Roosevelt died suddenly, poor Harry Truman was in the hot seat. But that is where I want to end the history lesson.

If any new President has had a disaster to confront, it is Joe Biden. Without fanfare or showboating Biden, too, has stepped up to the difficulties testing our nation.

Much like Truman and Lincoln before, 46 is grappling with a world in chaos, and a divided people at home. In another ironic twist, like Madison, Biden witnessed, a second violent desecration of the US Capitol.

To his credit, though his predecessor left a long trail of rubble, Biden understands the traditional role of Chief Executive, while clearly many Americans have forgotten, or worse, rejected. Biden is addressing the issues testing our country, not only for those who elected him, but those who did not. An American President can do no less.

Gail Chumbley is the author of the two-part memoir “River of January,” and “River of January: Figure Eight.” Both titles are available on Kindle. She has completed her second play, “Wolf By The Ears.”

gailchumbley@gmail.com