Steal This Letter #2

Let me be brief. What the GOP is attempting with this frivolous lawsuit concerning the 2020 election is dangerous and cynical. Party fidelity is certainly an American hallmark, but not at the cost of our political system. This dangerous precedent, pursued in a moment of expediency chips away at the foundation of our traditions.

The Constitution quite clearly established the rules on elections, and has endured since 1788. This moment of danger is more crucial to our nation than any excuse for undermining the transfer of power.

Clearly the steps taken by the Republican Party reveals an organization with nothing to offer. Ruthless partisanship is as much an epidemic as any virus.

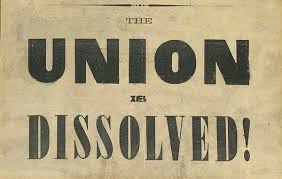

Each state has verified no irregularities in voting exist, choosing instead to act on one fallible man’s loose talk. The Framers did not dedicate their lives and fortunes to establish a government that dissolves on the whims of any person or moment. The United States relies on people of good will to respectfully honor election results.

As reluctant as I feel about using this analogy, Adolf Hitler was elected chancellor in 1933 in a free election, only to turn around and outlaw free elections.

Stop this now. Your party will lay in ruins if you forget who we are as a people. The process in presidential elections could not be clearer than stated in Article 1.

Gail Chumbley is the author of the two-part memoir, “River of January,” and “River of January: Figure Eight,” and the stage play, “Clay.”

A Burst of Joy

He looked an awful lot like Andrew Jackson. A long, craggy, narrow face, a shock of white brushy hair, and an irascible temperament. That was my paternal grandfather, Kurtz Olson. Despite his throwback, no-nonsense, narrow persona I found him endlessly interesting and somehow quite endearing.

The youngest of seven children to Swedish immigrants Peter and Matilda Olson, Kurtz was born in Wing River, Minnesota in 1905. Though I don’t know much about his early Minnesota upbringing, I do know that he had a mercurial temperament, no attention span, and restless feet. Grandpa frequently uprooted his family, first moving house to house, then state to state, reaching the Pacific coast.

During the worst of the Depression years Grandpa worked as a welder, and scrap metal dealer. My dad like to remind us that with so many people jobless, Kurtz had lots of work repairing and parting out junked automobiles. One of my favorite snapshots from his early years is Grandpa and another man posing with axle grease below their noses. The two were making sport of Hitler, who in the 1930’s was still viewed as an object of jest. Grandpa Kurtz is smirking, knowing he’s naughty, and thoroughly enjoying himself.

During the Second World War, he and my grandmother moved the family to Tacoma, Washington. With the “Arsenal of Democracy” in full swing, Kurtz had plenty of metal work on the coast. After 1945, he again uprooted and moved his family to Spokane, Washington, where cheap hydro power had opened plenty of post-war employment.

Still, Minnesota remained the holy land. Always impulsive, Grandpa would hop in his truck and make sudden pilgrimages home, blowing straight through Montana and North Dakota, usually 24 hours or so to reach the open arms of his Minnesota family.

For Kurtz it was as if traveling from Paris to Versailles, but a hell of lot further.

Unlike my immediate family, where I was the only girl, Kurtz lived in a decidedly female home. My aunt and grandmother typically sat for hours at the kitchen table, reading the Enquirer and movie magazines while talking shit about nearly everyone else in the family. Poor old Grandpa. Those two women tied that poor man into knots, riling him up with nonsense and fantom outrage.

It wasn’t that my Grandfather was unkind by nature, but he was easy to wind up, perceiving the world in black and white, dictated by those two judges presiding at the kitchen table.

Fortunately, despite those women bad-mouthing me, my brothers and the rest of the extended family he liked me. And I liked him.

In a fleeting, incomplete memory I see him waiting under street lights at the Spokane Greyhound bus depot. We all must have been meeting a relative from Minnesota or Seattle. In a burst of joy I remember shouting “Grandpa,” as I sprinted to him, where he scooped me up into a hug. Another vivid moment I recall was his truck pulling up in front of our house, and Kurtz coming to the door wearing nothing but that smirk, and bright red long johns, with laced Red Wing boots. What a character.

Speaking in a NorthAmerican Scandinavian cadence (yah, you betcha) made some of his comments worth remembering.

“First they call it yam, and then they called it yelly, now they call it pree-serfse.”

And Kurtz always had a dog. There had been Corky, Powder and Puff, Samantha, and Cindy among many others. Samantha was an especially smart Border Collie. After finding herself thrown on the floor of Grandpa’s truck one too many times, she figured out how to brace herself on the dashboard. He would roar up to yellow traffic lights, then stand on the brakes to avoid a red light. My god it was perpetual. My guess is he needed a new clutch about every three months, casualties of his Mr Magoo style of driving. At any rate, Samantha his wise co-pilot learned to watch the traffic lights and prepare for impact.

Pulling up to his house on some forgotten errand I saw my grandpa splitting wood in the backyard. Across the fence, next door, a neighbor dog set up a ruckus barking my way. I called out, “You be quiet over there,” to which my grandfather observed, “He doessent underschand you. It’s a Cherman Shepard.” Then he laughed, and so did I.

My children didn’t know Kurtz. And for that I’m sorry. They missed a true original. I suppose that is my job, and the job of all of us Boomers to share these kind of stories. We bridge the years between that Depression-era, World War Two generation to our Millennial children and our grandkids. They won’t know if we don’t tell the story. And since it’s December, I’ll sign off with this Kurtz Olson Christmas anecdote.

On Christmas Eve in about 1936-37, my grandpa packed up the family for an evening service at the Lutheran Church. Being good Swedes they had placed traditional candles balanced on the boughs of their live Christmas tree. Somehow in the bustle they left some candles lit. By the time they returned the house was gone replaced by a fully engulfed fire lighting up the night.

They lost everything. In an ironic twist my grandfather the welder somehow overlooked the flames of his yule-tree. That incident remained an inflection point in Olson family lore.

Now he’s long gone, as is my dad and other family members. But through the written word he remains as vivid as his humor, his voice, and his presence in my memory.

Merry Christmas.

Gail Chumbley is the author of the two-part memoir, “River of January,” and “River of January: Figure Eight” three plays on history topics, and a screenplay based on her books.

Set Their Feet On The Firm And Stable Earth

“Princes’ don’t immigrate” opined the 19th Century American magazine, Puck. The subject of the quote concerned the multitudes of immigrants flooding both American coastlines. Newcomers hailing from Asia and Southern Europe had alarmed American Nativists who considered the influx as nothing more than riffraff, and a danger to good order. Unfortunately this view of the foreign-born still endures today.

News footage over the last few years has chronicled the plight of the dispossessed amassing along southern tiers of both Europe and the US. Frequently victims of repressive governments, criminals, and crippling poverty, risk dangerous journeys, refugee camps, and even cages to escape hardships.

The earliest immigrants to American shores shared similar pressures, escaping the unacceptable familiar for an unknowable future. A brief look at the American Colonial period illustrates this enduring dynamic.

16th and 17th Century England targeted dissident groups in much the same way; exiling nonconformists, petty criminals, while others were lured by the hope of riches and a fresh start.

These emigres shared one common thread-remaining in England was not an option.

Religious challenges to the Catholic Church set in motion a veritable exodus of refugees fleeing England. As the Protestant Reformation blazed from Europe to the British Isles, the bloody transformation of the English Church began. In the 1535 English Reformation, King Henry VIII cut ties with the Vatican, naming himself as the new head of the English Church. This decision triggered a religious earthquake.

The Church still closely resembled Catholicism, and the disaffected pressed for deeper reforms, earning the title, “Puritans.” Ensuing religious struggles were long, bloody, and complicated. Ultimately the discord culminated in the violent repression of Puritans.

Two phases of reformed believers departed Great Britain for the New World. First was a small sect of Separatists led by William Bradford. These Protestants believed England to be damned beyond redemption. This band of the faithful washed their hands entirely of the mother country. Settling first in Holland, Bradford and other leaders solicited funding for a journey to Massachusetts Bay. Americans remember these religious refugees as Pilgrims.

Nearly a decade later another, larger faction of Puritans followed, making landfall near Boston. More a tsunami than a wave, the Great Puritan Migration, brought thousands across the Atlantic, nearly all seeking sanctuary in New England.

Lord Baltimore was granted a haven for persecuted English Catholics when that faith fell under the ever swinging pendulum of religious clashes. Maryland aimed for religious toleration and diversity, though that ideal failed in practice.

The Society of Friends, or Quakers, made up another sect hounded out of England. Britain’s enforcement of social deference, and class distinction, ran counter to this group’s simple belief in divine equality. Quakers, for example, refused to fight for the crown, nor swear oaths, or remove hats encountering their ‘betters.’ That impudence made the faith an unacceptable challenge to the status quo.

William Penn (Jr.) became a believer in Ireland, and determined the Crown’s treatment of Quakers unjust. After a series of internal struggles, King Charles II removed this group by granting Penn a large tract of land in the New World. Settling in the 1660’s, “Penn’s Woods,” or Pennsylvania settled the colony upon the egalitarian principles of Quakerism.

Scot settlers, known as Scots-Irish had resisted British hegemony for . . ., for . . ., well forever. (Think of Mel Gibson in Braveheart.) First taking refuge in Ireland, this collection of hardy individualists, made their way to America. Not the most sociable, or friendly bunch, these refugees ventured inland, settling along the length of the Appalachian Mountains. Tough and single-minded, this group transformed from British outcasts to self-reliant backcountry folk.

Virginia, the earliest chartered colony, advanced in a two-fold way; as an outpost against Spanish and French incursions, and to make money. At first a decidedly male society cultivated tobacco, rewarding adventurers and their patrons back home by generating enormous profits. Ships sailed up the James and York Rivers depositing scores of indentured servants, not only to empty debtors prisons, but to alleviate poverty and crime prevalent in English cities.

Transporting criminals across the Atlantic grew popular. The Crown issued a proprietary charter to James Oglethorpe, for Georgia. Oglethorpe, a social reformer, envisioned a haven for criminals to rehabilitate themselves, and begin anew.

All of these migrants risked dangerous Atlantic crossings for the same reason. Parliament and the Crown considered the Colonies as a giant flushing toilet. England’s solution to socially unacceptable populations, was expulsion to the New World.

Caution ought to guide current politicians eager to vilify and frame immigrants as sinister and disruptive. No one lightly pulls up roots, leaving behind all that is familiar. (Consider the human drama on April 1, 2021 where two toddlers were dropped over a border wall from the Mexican side).

Americans today view our 17th Century forebears as larger than life heroes, but their oppressors saw these same people as vermin–as dispensable troublemakers who threatened good social order. This human condition remains timeless, and loose talking politicians and opportunists must bear in mind the story of the nation they wish to govern.

*The Middle Passage was the glaring exception of those wishing to emigrate.

Gail Chumbley is the author of the two-part memoir, River of January, and River of January: Figure Eight. Both titles available on Kindle.

gailchumbley@gmail.com

Steal This Letter

If you feel like contacting your Republican Senators copy and paste this one. Tweak it for your own state and issues.

Senator,

Donald Trump’s stubborn refusal to face the reality of his election loss is as dangerous an assault on our nation as 911, and much more damaging than Pearl Harbor.

This election fiasco flies in the face of American traditions. General Washington sacrificed much of his personal happiness to found our nation. As America’s first president, he placed our republic above any personal comfort, and Washington’s legacy bears that out. When his officers suggested he take the reins of power, the general declined and went home to Mt Vernon.

In 1860 Abraham Lincoln preserved what Washington had begun, our Union. And though it cost him his life, the United States was Lincoln’s primary concern.

Both men, a founding father, and the savior of the Union, counted their interests as secondary, because America mattered more than any one man. Now, through a series of events, that responsibility has fallen to you. The GOP majority in the Senate can end this assault on our heritage, and you can make that happen.

Your forebears would be proud.

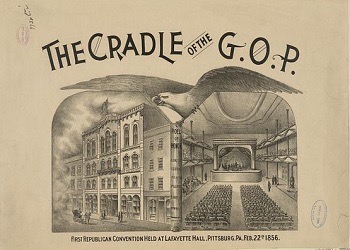

The Republican Party came into being on a noble, decent premise. It is the Party of Lincoln, not a lout from Queens.

*Please don’t patronize me with excuses.

Gail Chumbley is the author of the two-part memoir, “River of January,” and “River of January: Figure Eight.

gailchumbley@gmail.com

A Heady Moment

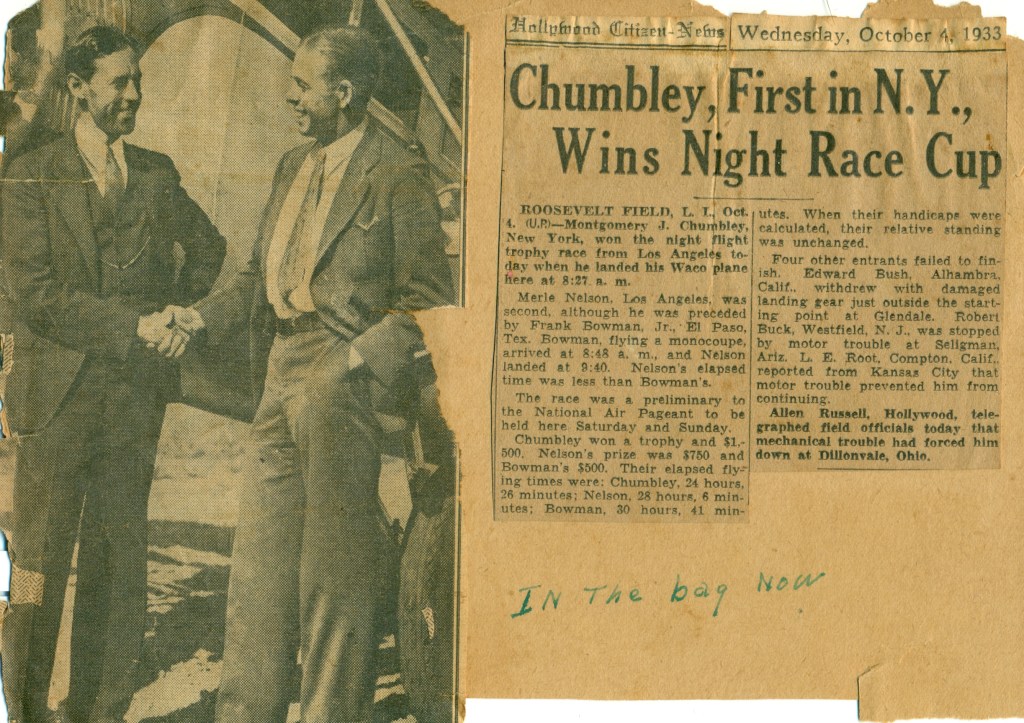

The night race kicked off “Roosevelt Field’s “National Air Pageant.” The event, chaired by First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, celebrated aviation and also raised funds for Mrs Roosevelt’s special charities. In addition, the Darkness Derby, competition, promoted “Night Flight” a new Metro Goldwyn Mayer film. The movie premiered at the Capitol Theater the following evening, and leading lady, Helen Hayes emceed the opening. And it was on the Capitol stage that Chum received his trophy from the actress.

This 1933 Transcontinental Air Race/Darkness Derby/Air Pageant/Film Premier, combined to make the moment a heady one for 24-year-old Mont “Chum” Chumbley. Armed with new friends and clients, and other air enthusiasts from the City, a promising future in flight lay before him.

Gail Chumbley is the author of the two-part memoir, “River of January,” and “River of January: Figure Eight.” Both titles available on Kindle.

gailchumbley@gmail.com

The Unforgivable Curse

Many of us have read JK Rowling’s Harry Potter books and/or watched the films. The author created a wondrous world of spells, incantations, and even included law and order via three unforgivable curses.

There are guardrails in this tale, and a bit of a messiah storyline. Harry willingly sacrifices himself, as had his parents and many others before. However, the “Boy Who Lived,” does, and returns to fight and vanquish wickedness.

Love, too, permeates the storyline, and the righteous power of good over evil.

But that’s not my take.

As a career History educator I came to a different conclusion; Harry Potter told me that failing to understand our shared past can be lethal. And that was the metaphor I preached to my History students.

Harry rises to the threat and defends all that is good and valuable in his world. If he didn’t, Harry could have been killed and his world destroyed.

It’s so apropos at this moment in our history to grasp our collective story as Americans.

Honest differences within the confines of our beliefs is one thing. Obliterating the tenants of democracy is quite another.

Americans cannot surrender our country to this would-be dictator, the things that have cost our people so dearly. Freezing soldiers at Valley Forge did not languish to enable DJT to trademark his brand to hotels, steaks or a failed university. The fallen at Gettysburg, and the suffering in Battle of the Bulge was not to pave the way for DJT to get us all killed from a ravaging plague. The girls who perished in the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, the miners murdered in the Ludlow Massacre, or humiliated Civil Rights workers beaten at the Woolworth’s lunch counter was not for Donald Trump to validate racism and sexism and undo labor laws.

He doesn’t know our nation’s history, and as George Santayana warned us, we are condemned to sacrifice all over again.

Vote.

Gail Chumbley is the author of the two-part memoir, “River of January,” and “River of January: Figure Eight.

gailchumbley@gmail.com

A Break In The Cover

Cloud cover continued to dog the exhausted flyer. Though dawn light saturated the sky, visibility hadn’t improved.

Whirring through the gauzy gray, he weighed his options. If the weather didn’t improve, he would navigate out over open ocean and look for a break in the misty gloom. This contingency plan set, Chum streamed eastward, nervously checking and rechecking his wristwatch.

From the corner of his eye, he spied a shifting break in the cover, and Chum didn’t hesitate. He pushed the yoke and slipped through the sudden gap.

A panorama of chalk-gray spindles greeted him. Automobiles the size of insects, inched along among the spires.The Waco soared above the Manhattan skyline.

Exhilarated and exhausted, Chum beelined over the East River, and on to Roosevelt Field.

Thundering down landing strip number 1, Chum slowed his Waco to a full stop, tired but satisfied he had prevailed.

But the race had not ended.

Officials rushed the tarmac, urgently shouting and waving. Concerned about the commotion, he reached to turn the throttle off, and that was when he heard a chorus of NO above the din. Frantic hands pointed in the direction to another landing strip. If he shut down the motor he would be disqualified. Without a word, Chum promptly taxied to landing strip number 2, then shut down his biplane.

He had won.

Seven planes had ascended into darkening California skies. Of the seven only three found their way to Roosevelt Field. Chum’s Waco cabin had journeyed above the sleeping nation in 24 hours and 26 minutes; two minutes added by his last minute dash across the field. His victory award-$1,500, enough to reimburse the stock broker, and pay off his airplane. Not bad for a young man struggling through the worst year of the Great Depression.

Gail Chumbley is the author of the two-pat memoir, “River of January,” and “River of January: Figure Eight.” Both titles available on Kindle.

gailchumbley@gmail.com

New York’s Lindbergh

Building his own charter service at Roosevelt Field, Mont Chumbley got right to work building a clientele. Though 1933 marked the low point of the Great Depression, photographers and reporters from the Associated Press, United Press International, continued to work, beating a path from Manhattan to hire his Waco. Adding student-pilots to his schedule, plus weekends barnstorming around the countryside, Chum made ends meet.

Friendships with other aviation boosters included Amelia Earhart, Broadway producer Leland Haywood, wealthy philanthropist Harry Guggenheim, and his first sweetheart, pilot Frances Harrel Marsalis. In a later interview Chum referred to a long ago passenger, Katharine Hepburn, as a ‘nice girl.’

By Autumn of 1933 Chum unexpectedly found himself a contender in a transcontinental night race, though it hadn’t been his idea. A prominent client who held a seat on the New York Stock Exchange believed Chum was New York’s answer to Lindbergh, funding needed modifications to his Waco C, if only the young man would enter. Chum, weighing his chances. finally agreed.

His biplane soon readied, Chum winged his way from Long Island to Glendale, California, flying much of the trip west by moonlight for practice. Resting in Los Angeles much of October 2, 1933, Chum was told he was seeded third for take off, and finally lifted his Waco into dusky eastern skies.

At his first stop, taxiing across a dark air field in Albuquerque, a fueler informed him another plane had already been and gone. A bit panicked, sure he was lagging behind, the young flyer hustled into the night sky, opening the throttle full bore to catch up. Just before dawn, the lights of Wichita appeared, where the spent pilot learned he was, in fact, the first entrant to arrive.

Weary as Chum felt, he couldn’t sleep. Keyed up by the excitement, he had to wait on those planes yet to arrive. And by late morning only two aircraft had cleared Albuquerque, a Monocoupe and a Stinson.

This night derby narrowed to a three-man contest.

Awarded 2 hours and 10 minutes for his first place in Wichita, Chum coaxed his Waco upward against the lengthening shadows of a Kansas sky. Hours later, at his last checkpoint in Indianapolis, Chum pushed on for New York.

However, the weather wasn’t cooperative.

Through western Pennsylvania, the bi-plane’s windshield began to pierce thickening clouds. Growing anxious, he thought he might be off course, or even worse, lost. But luck remained his co-pilot, when he glimpsed a small break in the inky mist. A lone light flickered below in the blackness, and he slipped down through the pocket.

Executing a bumpy landing on a farm field, the young flyer stumbled through darkness and dirt, making his way toward the light pole, and a modest farmhouse. Urgently thumping on the door, Chum roused a farmer and his wife, breathlessly apologizing for his intrusion.

Explaining his predicament the bewildered couple kindly let him in. As the wife perked coffee, and laid out food, the farmer got out his maps and showed Chum his location. With heartfelt thanks, he apologized once again, then returned to the night sky, righting his direction toward New York and hopes for victory.

Gail Chumbley is the author of the two-part memoir, “River of January,” and “River of January: Figure Eight.” Both titles are available on Kindle.

gailchumbley@gmail.com

Mr Jefferson, Mr Hamilton

Are all the laws but one to go unexecuted, and the Government itself go to pieces lest that one be violated? Even in such a case, would not the official oath be broken if the Government should be overthrown when it was believed that disregarding the single law would tend to preserve it? A. Lincoln, July 4th, 1861

The roots of the United States Constitution can be traced back to the sparkling salons of Paris and the intellectual circles of England. Termed the Age of Enlightenment, the era produced farsighted treatises and essays, that later influenced the principles of American law.

One discussion pondered the character of humanity. By simply breathing air were all guaranteed fundamental rights? Was every person, by nature, competent to participate in the political process? In other words, if left unbridled, could citizens mutually ensure good order among themselves?

Philosophers John Locke and Charles-Louis Montesquieu believed in that innate goodness. To their way of thinking, people, left in a state of nature, could be trusted, guided by enlightened self-interest. A limited central government best served in this model, trusting in individual virtue.

In the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson nearly plagiarized Locke, justifying the causes for the break with Great Britain. The “Sage of Monticello” explained that Parliament had failed in protecting freeborn British Colonials, and argued that it was a duty to establish a better system that did.

Jefferson’s interpretation meant free landholders stretching across the vast continent required no political coercion. Government, in this scenario, left all persons in peace, limiting a federal system to foreign policy, tariffs and other national issues.

Jefferson’s political adversary, Alexander Hamilton held a starkly different view. Having come into the world without any standing, Hamilton rose in society by his own wits, and smarts. One had to earn the right to shape public policy. Hamilton championed a strong central government, endowed with enough power to found a stable nation-state. Economic authority, in particular, the power to tax, float bonds, and regulate tariffs was his prerequisite for lasting stability.

In practice, by 1781, each state functioned as independent fiefdoms, loosely held together by the Articles of Confederation. Chaos abounded. The various states battled over countless rival interests. A failure to levy taxes especially crippled the nation’s ability to function.

From Hamilton’s perspective the nation would collapse if nothing was done to curb mob rule. Violent acts flared throughout the fledgling nation. From credit to taxation, Hamilton understood, without a healthy economy philosophical differences were moot. So with real alarm Hamilton vented to a political foe, “your people, sir–your people is a great beast.”

What good was victory at Yorktown if America failed to function? The British could bide their time and reoccupy when the country eventually collapsed. In fact, war heroes like Ethan Allen were reaching out to the British in Canada, to protect settlers in Vermont, and land promoters in the south opened similar talks with Spanish.

Young Hamilton too,had borrowed liberally from Enlightened philosophers.The theories of Englishman, Thomas Hobbes especially persuaded the New Yorker that people required a strong central authority. Impetuous citizens and resisting states posed a far greater threat than any adversary.

When the Constitutional Convention finally adjourned in September, 1787, the product of their work, the US Constitution fused Hobbes, Locke, and other philosophers of the Enlightenment. A new creation like no other ever.

Jefferson, fresh from Paris, flipped out a bit reading the new framework. He argued that the document must remain limited, exercising narrow authority. Hamilton argued for a much broader reading, insisting that ‘implied powers’ made the Constitution flexible.

This difference established the first political parties: The Democratic-Republicans under Jefferson, and the Federalists under Hamilton.

Americans still find a home somewhere between the beliefs of Mr Jefferson and Mr Hamilton. Except for the great beasts who overemphasize their 2nd Amendment rights to attack the halls of government, and wage war upon us all..

Gail Chumbley is the author of the two-part memoir “River of January,” and “River of January: Figure Eight.” Both titles are on Kindle.

gailchumbley@gmail.com