You know, that time the kids and I appeared in the Washington Post Sunday Magazine.

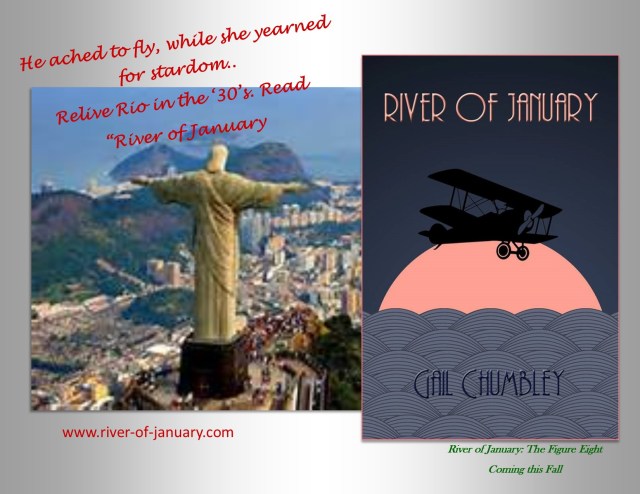

Gail Chumbley is the author of River of January, a memoir. Also available on Kindle.

Look for volume two, “River of January: The Figure Eight,” due out this Fall.

You know, that time the kids and I appeared in the Washington Post Sunday Magazine.

Gail Chumbley is the author of River of January, a memoir. Also available on Kindle.

Look for volume two, “River of January: The Figure Eight,” due out this Fall.

Hi Gail,

Allie McKinney Content Project Operations Manager BiblioLabs 100 Calhoun Street, Suite 200 Charleston, SC 29401

Gail Chumbley is the author of River of January. Also available on Kindle

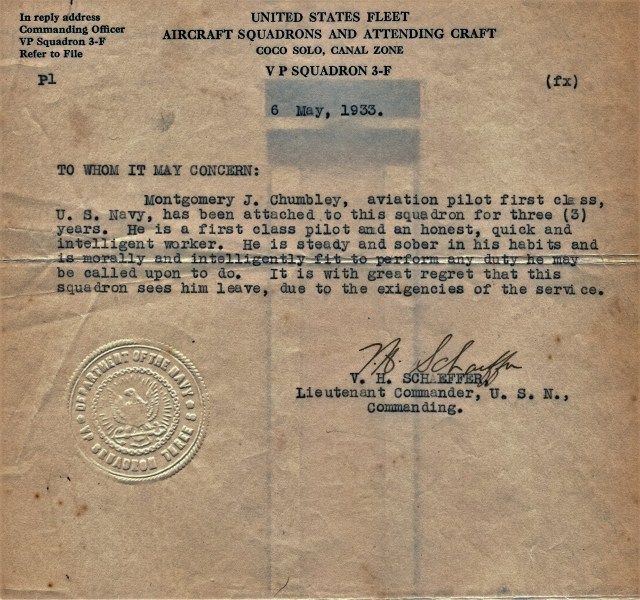

In River of January and the sequel, The Figure Eight, (in progress) Mont Chumbley repeatedly insists the number 13 is lucky for him. In that spirit “Chum” left the US Navy on June 13, 1933, his 24th birthday, to pursue a career in civilian aviation. Today would be the pilot’s 107th birthday. For more of his fascinating story read River of January, available in hard copy and on Kindle.

River of January‘s Free Kindle Weekend!

Enjoy a read on the house compliments of Kindle. Available from Saturday morning through Monday night.

When you’re done tell a friend, and say something nice on Amazon Reviews!

Gail Chumbley is the author of the memoir, River of January. Also available on Kindle.

This letter, one of hundreds of documents used in River of January, marks Chum’s first discharge from the Navy in 1933. This letter speaks highly of the young man who five months later would prevail in the “Darkness Derby,” continental air race.

Gail Chumbley is the author of the memoir, River of January. Available on Amazon and Kindle.

Peppered through the vast family archive used in the writing of River of January, exist three special sets of letters. Though largely filled with conventional chatter and sentimental superlatives, these documents also provide a fascinating peek into another time and place–of a nation suffering through economic free fall, and perched on the threshold of war.

The letters frequently mention the turbulent state of international affairs, from fascist Italy, to the Spanish Civil War; episodes that eventually and inevitably led to the Second World War. Even more ink is expended discussing the difficult economic situation stemming from the fallout of the Stock Market Crash–securing theater bookings, closing business contracts, and aviation training in a downsized Navy. Still, aside from the monumental, most of the content reported simple day to day life, shared with humor and concise observations. From their correspondence these men clearly promoted themselves, vibrantly rising from the faded and yellowing paper.

The first are a series of letters mailed from a Hollywood address, composed by comedy writer, Grant Garrett. (See above). The second collection, posted almost exclusively from Europe, came from the hand of a 28-year-old Belgian entrepreneur, Elie Gelaki. Serious and painfully formal, Elie’s letter reveal a methodical mind, clearly continental in manner with a determined nature. Finally, the last, and largest collection came from Mont Chumbley, Virginia farm boy turned aviator, who looms largest in the memoir. His writing reveals a practical, warm, and straightforward young man who expressed himself in plain language.

Despite definite differences in style, these three writers did share many qualities. All were deeply ambitious, establishing successful careers in the particularly difficult years of the Great Depression. They were clearly literate and educated, in a time when many (at least in America) did not regularly attend nor graduate from secondary school. These letters rise from the ordinary, written with distinctive originality, candor, and technical accuracy.

The link that tied this portion of the archive together was the beautiful New York dancer who received each letter, and preserved them all, Helen Thompson.

Grant Garrett became Helen’s first heartthrob. A native of Los Angeles, Garrett was a regular script contributor to radio shows and vaudeville acts. A talented singer and dancer in his own right, he interviewed Helen to partner with him for an upcoming tour across the country in 1931. After their junket ended, she returned to New York, and he returned to Hollywood. Now in love, the couple exchanged a series of clandestine letters, (her mother forbade Helen to see him again) with only Grant’s compositions still surviving today.

For a nineteen-year-old girl, Grant was hard to resist. Moody, smart, and funny . . . he was the essence of the tortured poet, a perfect combination of beauty, pain and passion. Of her suitors, Grant was the only one who shared her profession, and their time together forged a strong, and influential bond. Helen’s association with Grant provided something of a professional finishing school for her. From Grant she learned to laugh through tough times, and push through adversity because “the show must go on.”

Grant’s whimsical map of a planned Garrett & Thompson reunion tour.

Next time, Belgian, Elie Gelaki.

Read more about Grant Garrett, Elie, and Mont Chumbley in River of January, available in hard copy and on Kindle.

“So you’ve been to see all the big boys, eh?” commented a sales representative from Long Island who was seated behind a battered old desk. Airplane distributor Howard Ailor of Waco Aircraft studied the young man’s face. “And by the looks of you they all turned you down.”

“That is about right, Mr. Ailor.” Chum responded, trying to look confident. “I was hoping you might know of something out here, maybe something at Roosevelt Field.”

“I don’t know you, son, but let me give you some advice. Don’t dawdle around hoping for that phone call. This is no economy to sit by and wait for miracles. You’ll starve first. Push your way into the air business with your own equipment, that‘s what I say, and I can help you with that. We have some beauties right here on site.”

Chum listened to the silver-tongued salesman, surprised that he agreed with all Ailor had to say.

Chum also realized that he had returned to an America deep in the throes of financial depression.

Economic life in the 1920s had played out as a frenzied, unregulated party. By all appearances the country had embraced infinite prosperity. Insider trading and other shady practices reigned on Wall Street, where market manipulators pooled cash and bought up stock, artificially driving up values. Regular folk, believing they were on to something big, bought these tainted stocks as crooked investors dumped them, reaping fabulous profits.

Indiscriminate buying, using easy credit, pumped the overblown Dow Jones to ballooning artificial heights. Even private banks joined the frenzy, wagering the savings of their account holders to increase their own bottom line.

This facade of spreading affluence ensured the “hands off” economic policies accepted in Washington. Then the market imploded. On October 29, 1929, “Black Tuesday,” the savings of a nation disappeared with the steepest financial crash in American history. Thousands upon thousands of people were ruined and the enterprise of a nation dried up.

Young Mont Chumbley had resigned from the Navy without another job, and now found there were none. The pilot’s only and best assets were his optimism, his pluck, and an old Chevy.

“Over here,” Ailor directed Chum, as they walked toward a hangar housing a red-with-black-trim Waco cabin biplane. “This baby’s a real beauty, right? We can take it up for a spin, if you like, but you can’t have this one—it’s spoken for. Still cough up a down payment and we’ll order you a new one. It’d be here in only six weeks.

“I came here looking for a job—and you want to sell me an airplane?” Chum blurted in disbelief.

Ailor continued to rattle on as though the pilot had not spoken. “Hell! I’m feeling generous. I’ll even let you rent office space right here on Roosevelt Field for a percentage of whatever you earn as you get your footing.”

Chum realized he had never encountered such a smooth operator. Ailor finally faced the boy. “Look, you can’t negotiate with reality, son. And the reality is that there are no jobs. The country’s flat busted.”

Chum knew his mouth hung open in reaction to the salesman’s bald audacity. But he also knew he agreed. Ailor was absolutely right.

Chum needed to find a way to buy that airplane. It appeared to be the only real option open to him. With little money left from his dwindling resources, he found a Western Union office and cabled his mother in Pulaski for help. He hadn’t written or visited much since joining the service and felt badly his note only asked her for money. However, Martha didn’t complain or hesitate.

“I’ll run down to our bank in town—still solvent, doors open,” she wired him right away. “A thousand, Mont? Is that enough? Where should I wire it?” Martha would still do anything to help her boy.

River of January by Gail Chumbley available at www.river-of-january.com and Amazon.com

Only six years had passed from Lindbergh’s Atlantic flight, when Chum won the cross-country Darkness Derby in October of 1933. Public wonder and oodles of press coverage followed aviators across the country, and around the world. Pilots were viewed as rustic pioneers risking the unforgiving rules of gravity. Hustling for every penny, Mont Chumbley used his rare talent for more than business, offering lessons during the week, and moonlighting weekends entertaining an aviation-crazy public.

County fairs proved a reliable source of pocket money, and he beat the bushes to find well attended events. In good weather he could charge $5 dollars for three passes over local fairgrounds; enough for gas, dinner and a little left over for his time.

It was on today, May 16, back in 1933 that Chum flew his Waco biplane to a fair in Binghamton, New York. He traveled north from New York looking for a little fun, and maybe a few extra bucks. He hit gold that day when he met up with famed parachute jumper, Spud Manning. Now Spud was a young guy, too, and much like Chum, had to make his luck to survive in Depression-era America. So what this enterprising gent challenged, was jumping from airplanes.

With Chum soaring at 15,000 feet, Manning, harnessed in his chute, clutched a bag of flour to his chest. In his fall Manning released the contents to trace his descent. The 25 year old’s shtick was to risk death by falling until the last possible moment, somewhere around 1000 feet, to pull his ripcord. He succeeded to scare the hell out of patrons and they paid him to do it again.

Presumably Spud carried out his jump the same way on that May 16th in Binghamton New York. Leaping for profits, Spuds and Chum performed the stunt as long as it paid. Spuds leaped into the sky, likely accumulating a dusty, white face as the flour plumed up from his arms. Rolling on the ground, grappling with his chute, he jumped to his feet delighting the dazzled crowds.

That May 16th must have left hundreds of Binghamton fair goers in awe. Clear blue weather, excited customers, viewing their landscape from the Waco in three memorable passes; all capped off by the heart stopping jumps of Spud Manning.

Sadly, Chum’s afternoon associate had less than four months to live. Spud was killed that September when, as a passenger on experimental aircraft, he crashed into Lake Michigan. His body and two others washed up on shore ending a massive search over the water.

Chum clearly understood death accompanied each flight, but he loved flying more than dwelling on his fears. Presumably Spud Manning too, resigned himself to the possible price of repeated defiance to the forces of gravity.

Somehow the miracle of the sky rendered the hazards irrelevant.

Gail Chumbley is author of memoir River of January