Preaching in 1630, Massachusetts Bay Governor John Winthrop, declared the new Puritan settlement a godly utopia, “A City on a Hill.” Since that time Winthrop’s assurance of purpose and perfection has shaped the narrative that is American history. For over two centuries the United States pushed forward striving to make real those founding aspirations. Many Americans, either in groups or as individuals have fought the good fight to extend liberty for all: the most notable example being the abolition of slavery. Yet the path toward realizing the dream of heaven on earth has been many times interrupted with progress’s nemesis—armed warfare.

As Revolutionary War zeal subsided in the late 1700’s, a series of remote camp meetings sparked a movement called the Second Great Awakening. (Yes there was a First) The popularity of these rousing evangelical revivals lit an impassioned fire that called Americans, mostly Northerners to eradicate sin in the shiny new republic. Determined reformers such as Charles Grandison Finney, Frederick Douglass, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton labored tirelessly to rid America of her shortcomings; drunkenness, degrading of women, punitive treatment of the mentally ill, racial inequality . . . in order for the country live up to its charge as a “called nation.”

Despite the diversity of causes and legions of faithful supporters, slavery alone came to dwarf all other movements and to ultimately divide the country. Early instances of violence in the effort to end slavery offered a taste of the violence to come in the Civil War; Abolitionist-editor, Elijah Lovejoy was shot dead in the doorway of his newspaper office, while another anti-slavery editor, William Lloyd Garrison found himself tarred and feathered repeatedly by those who hated his militancy. Zealot John Brown hacked to death five pro-slavers in an episode known as “Bleeding Kansas.” In these instances, “the writing on the wall” had truly been composed in blood.

When hostilities began in April, 1861 the energy of a nation fixated on the course of each battle, fear and resolve ebbing and flowing with each outcome. The shape of America’s future waited in the balance. Finally, after four ghastly years of bloody fighting, Southern hopes of an agrarian, slave-ocracy died, and as President Lincoln so eloquently phrased it, America found “a new birth of freedom.”

Left unaddressed were those other reforms, forgotten in the war. The mentally ill remained behind bars, incarcerated alongside dangerous criminals. Women were legally considered wards of their husbands, with no more standing than dependent children. Countless young children toiled endlessly in textile mills and coal mines, exploited by owners, deprived of any chance for an education. And the legions of former slaves faced a new form of slavery, Jim Crow and sharecropping.

Reform again gathered momentum in the late 19th Century. Aiming once more for that ‘city’ aspiration, the Progressive movement took shape, carried on by a new generation of the faithful, imbued with a sense of social justice to confront the many wrongs left unaddressed from an earlier time, and new issues related to urban growth. Notables from this post bellum movement include; Jane Addams, one of the founders of American Social Work, writer Upton Sinclair and his shocking expose’ The Jungle a condemnation of the meat industry, and John Dewey who normalized public education with coherent curriculum’s and compulsory school attendance. Dewey believed, as had the founders of America, that the nation relied upon and deserved an educated electorate to safeguard the promise of America into the future.

This movement found a great deal of success in improving the country and the lives of its citizens. Building safety reform came on the heels of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire in 1911. The Jungle brought about the establishment of the Food and Drug Administration, while political reforms included the secret ballot, limiting “Bossism,” and other forms of political corruption.

Then, in 1914 Europe went to war. By 1916 Progressive President, Woodrow Wilson committed America to join in, asking for a declaration against Germany, sending American soldiers into the trenches. And once again, when the guns silenced progressive reforms disappeared as if they had not existed. On the imaginary road to “Normalcy,” the wealthy and powerful misused the country as a personal piggy bank, plundering and cheating with no legal check.

After a decade long litany of economic abuses tanked the Stock Market in 1929, the nation once again turned toward progress, this time on an unparalleled scale. The advent of Franklin Roosevelt and his wife, Eleanor, to the White House marked a revitalization of reshaping America to benefit all Americans. The New Deal remembered for its alphabet agencies, aimed to recover the devastated economy and ward off future abuses that had nearly destroyed the well being of the Republic.

America’s entrance into World War Two bucked the pattern of a reactionary pushback. FDR remained at the helm, until Harry Truman took the reins of government, continuing the tradition of affirming change. GOP President Dwight David Eisenhower kept a moderate hand on the tiller, particularly in the realm of Civil Rights, enforcing the Brown V. Board of Education decision to desegregate public schools.

But with JFK’s murder, the wheels once again came off social progress. As much as LBJ tried to give America all he could; The Civil Rights Act of 1964, The Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Highways Beautification Act, Head Start, Medicaid, and many more pieces of his Great Society legislation, Vietnam eroded all the good.

That endless nightmare of a stalemate in Southeast Asia worked at cross purposes for bettering society. The daily body count, student protests, war atrocities, such as the My Lai massacre, or the shock of the TET Offensive in 1968 sapped America’s desire to do anything but find a way out of the jungle.

Promoting the general welfare came nearly to a complete halt by 1980. The advent of the Reagan Revolution, and subsequent downsizing of the federal government left the vulnerable largely on their own. School lunch programs were cut, the mentally ill let out on the streets of America, while the armament industry threw the nation into deep deficits.

On this Memorial weekend it might be good to consider the potential of America when at peace. Trapped today in an endless cycle of war, this nation struggles to find her soul, to embrace together the light of our national promise. Two military presidents, our first, General George Washington and our thirty fourth, General Dwight D. Eisenhower pleaded with America in their farewell remarks to avoid war as the worst use of our best abilities. Both men, forged in the adversity of difficult wars, recognized the wasteful distraction and deadly allure of war. Washington cautioned against “entangling alliances, and Eisenhower “the military-industrial complex.”

Ultimately, those who know war grasps what is truly lost. Every weapon produced in a munitions factory most certainly casts a wrench into the wheels of human progress. Winthrop meant his reference from the book of Matthew to inspire an example to the world. Forcing Americanism by the barrel of a gun is born to failure, achieving nothing lasting but resentment abroad, and stagnating injustice at home.

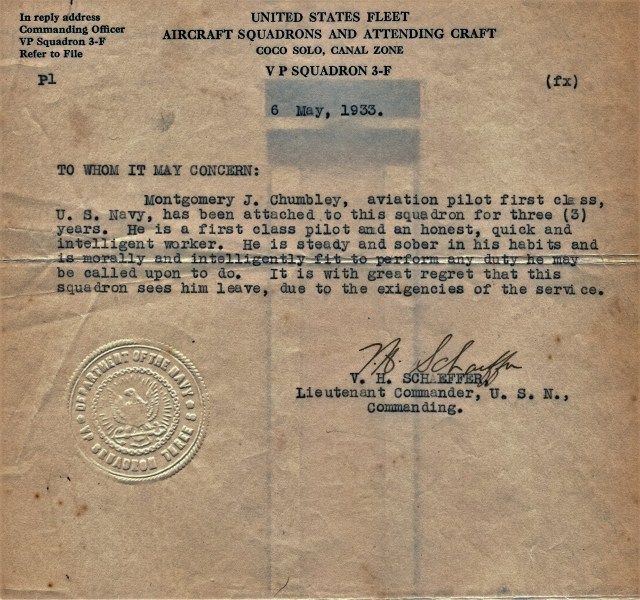

Gail Chumbley is the author of the memoir, River of January, also available on Kindle.