In order to be clearly understood one must write.

G Chumbley

In order to be clearly understood one must write.

G Chumbley

By Lex Nelson

An avid history junkie from a young age, Gail Chumbley never meant to be a writer. She spent the first half of her life clocking in 33 years as an American History teacher before retiring from Eagle High School in 2013. Along the way, she married Chad Chumbley, who, she said, told stories about his father the pilot and his mother the showgirl, which were almost too fantastical to be true. Favorite accounts included how Montgomery “Chum” Chumbley and Helen Thompson met in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where Chum sent a note backstage; the time Helen acted alongside Bela Lugosi before turning her sights to ice skating; and the day when Chum, not yet a World War II pilot, shared his cockpit with Katharine Hepburn. Eventually, Helen’s dancing career and Chum’s military service disrupted their marriage.

The stories were true, confirmed by endless boxes of photographs and papers Chad had saved and an oral history Gail conducted with her father-in-law before he passed away. While Gail found the tale of star-crossed lovers compelling, it wasn’t until Chad was diagnosed with throat cancer in 2010 that she decided share it.

Sitting at the kitchen table in her Garden Valley home, Gail opened up about the eight years of writing and research that resulted in two self-published books—River of January (2014) and River of January: Figure Eight (2016)—and a movie script. Chad, largely recovered from his cancer, sat in, and her script writing partner Ray Richmond joined the conversation by phone from Los Angeles.

Ray, let’s start with your role. What got you on board with turning Gail’s books into a script?

Ray: I could see [the story] on a screen when I was starting to read it. We have a pioneer aviator, we have a dancer from the golden age of entertainment and vaudeville and, you know, my only questions when I was reading were how [Helen] had managed to avoid murdering her mother, because I thought, this woman is just a natural, wonderful villain … and why this movie wasn’t made 20 years ago. It’s got the war as a backdrop, it’s got Hollywood, it’s got all of these great names in aviation, it’s got a little bit of Amelia Earhart, a little bit of Howard Hughes. It’s like history just jumps off the page.

Was it difficult to combine two books into one script?

Ray: Not really. It’s mostly about the second book … It’s really about their relationship and the whole backdrop [of WWII]. There’s a lot of female empowerment and disempowerment here. And there are so many different tentacles to that, because you’ve got the meddling mother-in-law who knows best, and the problem is, she really does know best, but she’s a harridan and horrible in the way she comes across while she’s conveying it. She did know that her daughter shouldn’t be with this guy who wanted a traditional life, and that [Helen] was destined to be a great dancer.

Gail, how did you make the decision to start writing your in-laws’ love story?

Gail: I’d look at [the photos and papers] and put them back and say, “I’ve got to write this book.” I meant it, and I didn’t mean it. I knew I should, but I didn’t know how. Then Chad got so sick and nearly died—he was in the ICU for eight days. I won’t let him show you his belly, but it just ran out of real estate for all the stuff they had hooked to him … it was horrible. I didn’t know what to do with any of that. Teaching worked to a point, because that’s sort of my living room, and I could really get comfortable, but when it came right down to it, I had all this unvented anxiety and fear and just PTSD. And I knew it. I knew I was crazy, and I knew I was feeling really nuts. When I got home at night, I was just a wreck. So the summer he started chemo and radiation … I was sitting up here every day going through all these letters, trying to make sense of it. [The draft] was horrible, and [my editor] fired me, but I wouldn’t give up because I couldn’t. I had no choice. I read Ron Chernow’s biography of [George] Washington, and there’s a line there he used that really resonated with me. It’s “the clarity of desperation.” I had the clarity of desperation.

You ended up writing the books.

Gail: I wanted someone else to [write Chum and Helen’s story] so badly. I tried to talk a bunch of people into doing it for me that were really good writers, but it’s like, you’re going into labor and no one else is having that baby. You’re going to do it. No one else was going to do this. It fell to me, and in a way that was wonderful, and in a way, it was a sentence.

What was it like transitioning from teaching to being a writer?

Gail: You hear about people who are in the military or the public service, and they retire and decide to teach. And I always thought, ‘Are they crazy? It’s hard work!’ Now, that’s rich. I go from one hard job, thinking writing would be a nice way to pass my job retired—and that’s hard work! I mean, there is no easy cheesy way to go into your retirement.

What was the research process like, going through Helen and Chum’s old papers?

Gail: The history part wasn’t hard for me. What was hard was to give voice to Helen, to give voice to Chum. Now Chum was easier, because I interviewed him. I had like 15 hours of oral history with him, and I knew him. I didn’t know Helen [who died in 1993].

But considering what happens at the end of the books, there must have been some difficulty in talking about Helen and Chum as parents.

Gail: [Chad] didn’t have a very happy childhood in that house … I think there’s something to that, sometimes really famous people are really lousy parents. Chum and Chad ended up very close though, because he died here, he died in Boise in 2006, and Chad was there every day.

Will you ever write another book?

Gail: I’ve thought about writing a book about generals who were very jealous of each other in wartime, and how those personal quirks and jealousies impeded the war effort. Like between Henry Halleck and Ulysses S. Grant … I feel like writing is the most basic form of communication that you can share without speaking, it’s as unique as a person’s fingerprint, and I think it’s really cool to do.

And Ray, what’s next for the script?

Ray: Well, what’s next is that I have some contacts at the Hallmark Channel, and I’m trying to convince them that they don’t need to make every movie about Christmas … But I really feel good about this. If it’s a great story and it’s meant to be, and it’s got so many vivid elements to it and such great characters, it’s going to be done.

Note: My students used to ask how the planter aristocracy persuaded poor whites to fight for their interests in the Civil War. I think the answer lies in the power and position that the underclass envied and hoped to attain.

Please permit me to reintroduce these four figures from America’s antebellum period.

Thomas Jefferson Best recognized as the author of the Declaration of Independence, the third president of the U.S., and the man behind the 1803 purchase of the Louisiana Territory.

Andrew Jackson The celebrated hero of the Battle of New Orleans, noted Indian fighter, and seventh president of the U.S.

John C. Calhoun Congressman, turned Senator from South Carolina, who served two separate administrations as Vice President.

Jefferson Davis, a former soldier in the Mexican War, one-time Secretary of War, and later President of the Confederate States of America.

These four men forged political careers prior to the Civil War that fully embraced the social norms of early America. To a man, all hailed from the Old South, where each man shaped distinguished reputations, built spacious mansions, entertained illustrious guests, all on the backs of slave labor.

Ironically if one asked these men’s occupation, not one would have mentioned politics. Instead, each would have replied, “I am a farmer.”

To modern ears that answer feels a bit misleading and absurd. However, in the early nineteenth century, exercising dominion over large tracts of land, and cultivating crops as far as the eye could see, was viewed the most noble and honorable of pursuits. But a gnawing truth lay behind the practiced manners and broad, fertile fields. A profound self deception had also taken root, sowing an overblown sense of racial superiority, and human oppression of nightmarish proportions.

That these “farmers” were all slave masters is the cruel truth–Lords of the Lash, who derived a living “wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces,” (As Lincoln so eloquently phrased).

These four planters also minimized the brutal underpinnings which sustained each man’s fiefdom. Jefferson, Jackson, Calhoun, and Davis capably hijacked, and sheltered behind “republican virtues,” including freedom and the social contract to suit their own interests.No higher authority held any sway over these planters–they were marked as privileged.

The patriarch of this sophistry was Thomas Jefferson.

Esteemed as the “Sage of Monticello,” Jefferson brilliantly articulated a vision of America where all lived freely upon private land, untroubled by outside interests. Residing upon acres of personal liberty, this master managed his estate immune from any overreaching government. For Jefferson, he and his fellow planters were the “natural aristocrats,” of the new nation, meaning they held the only legitimate claim to power. Only the elite of the community, like Jefferson, knew what was best for all.

The Sedition Act, passed by Congress in 1798, moved Thomas Jefferson to show his true political colors. President John Adams had wanted to silence political critics of his administration, and jammed this dubious legislation through Congress. In reply Jefferson authored a protest titled the “Kentucky Resolution.” In his tract, submitted to the Kentucky Legislature, Jefferson introduced the concept of ‘nullifying’ Federal law. Specifically, when a majority of state delegates, assembled in special convention, renounced a Federal statute, the law was rendered null and void within that state.

For the first time, in one pivotal moment, Jefferson’s insidious principle found its way into the bloodstream of American politics.

Ironically Andrew Jackson didn’t care for the intellectual, and philosophical Jefferson. Still, despite temperamental differences, Jackson did share Jefferson’s world view of complete dominion over his land and “people.” A ferocious master, Jackson answered to no civil law, but his own. Dabbling in both horse and slave trading, Old Hickory frequentlyoften challenged any man who questioned his conduct or honor.

To his credit Jackson did not pretend to care about high brow thinking or civic virtue. His philosophy was simple; the master was never wrong.

Before Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina soured into a states’ right’s militant, his political outlook had been national in scope. With unusual candor a very young Congressman Calhoun self-consciously confessed that slavery was a “necessary evil,” vital to South Carolina’s prosperity. But his marriage to a wealthy Charleston cousin elevated his social status, which in turn, adjusted Calhoun’s thinking. Assuming the role of a gentleman, while cultivating a prominent political reputation, Calhoun also became a slave master. Much like Jefferson’s Monticello, or Jackson’s Hermitage, Calhoun’s plantation, Fort Hill, was an ever-expanding operation, endlessly renovated using teams of slaves who also tended his fields.

In 1829, as Jackson’s new Vice President, Calhoun quickly butted heads with America’s new President. Steadily embittered by Jackson’s arbitrary, monarchial style, and indifference to law, Calhoun resigned the vice presidency and returned to Fort Hill an angry man. His stance on slavery hardened as well, leaving him a vitriolic defender of the practice. Under increasing pressure from Northern abolitionist, Calhoun, picked up his pen and insisted that slavery was not evil after all, but a ‘positive good.’

When Congress passed a protective tariff for northern goods, this former Vice President organized a state convention to fully resist the new Federal law. Calling his defiance “nullification,” Calhoun put into action Jefferson’s “resolution” that refused obedience to Washington.

Fortunately this particular crisis was averted by cooler heads in Congress, delaying the curse of fraternal bloodshed for a later generation.

By 1860 nullification had bloomed into full secession. No longer would the planter class tolerate insults or challenges to their natural superiority and authority.

It came as no surprise when South Carolina became the first of the eleven states to secede from the Union. Delegates attending a state convention in Columbia did not wait for the final electoral results to reject the election of Abraham Lincoln. So enraged were these aristocrats that Lincoln’s name had not even appeared on the ballot in most southern states.

I’ve added Confederate President Jefferson Davis to this piece because of his later role in perpetuating the genteel myth of the South. After four years of bloody battle and countless bullets finally settled the issue of Federal authority, Davis, released from jail began a writing career. He first penned, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, followed later by A Short History of the Confederate States of America. In both of these works, Davis invented a romantic world of gentlemen, belles, and contented slaves in the fields. The fantasy was bunk, but Davis, the onetime master of of Belvoir, and Brierfield, Mississippi, somehow got in the last word.

Davis’s fanciful yarn was only concocted as a charming fable to disguise a legacy of hubris, power, greed, hate, racial exploitation, and violence.

In answer to the question posed by my history students, poor whites defended the southern gentry because they wished to live just like them.

Gail Chumbey is the author of the two-part memoir, “River of January,” and “River of January: Figure Eight,” available on Kindle.

gailchumbley@gmail.com

“Our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.”

Had a six-plus hour drive today; Salt Lake City to my mountain cabin in Idaho. Lengthy car-time, for this Indie writer, always results in exploring fresh ideas for book marketing. I don’t say much to my family, but promoting the two-part memoir, “River of January,” and “River of January: Figure Eight,” is never far from my thoughts, and I’m pretty sure this is true of fellow writers.

Finally made it home, chatted with the husband, did a little of this and that, then idly picked up today’s newspaper. Now, I’m not an avid follower of the mystic, but being an Aquarian, (there’s a song about us, you know) I sometimes do indulge. And, as you can see the cosmos told me to do this, so by damn, I am.

Dear reader, if you enjoy a true American story, set in the American Century, get River of January and River of January: Figure Eight. In the pages, you will experience adventure, travel, glamour, and romance. Aviation enthusiasts relive the thrills and peril of early flight, theater fanciers follow an aspiring dancer as she performs across international stages, and takes her chances in Hollywood.

Take it from the author–in peacetime and in war–this two-part memoir is richly entertaining.

http://www.river-of-january.com. Also available on Amazon.com

Gail Chumbley is an award winning instructor of American history and the author of the two-part memoir, “River of January.”

We all know the story.

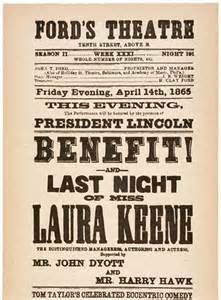

On a mild April night, President and Mary Lincoln attended the final performance of the popular comedy, “Our American Cousin,” at Ford’s Theater. Lincoln, by all accounts was in a light, blissful mood. A week earlier Confederate forces commanded by Robert E. Lee had surrendered at Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia, and except for some dust ups, the Civil War had ceased. We also know that John Wilkes Booth, and fellow conspirators plotted to kill, not only the President, but the whole order of presidential succession; Vice President Andrew Johnson, Secretary of State William Seward, etc . . . but only Booth followed through with that night’s violence.

Andrew Johnson took office in a whirlwind of shifting circumstances. In the year up to President Lincoln’s death a notable power struggle had taken shape between the President and Congress. America had never before endured a civil war, and the path to reunion had never been trod. As President, Lincoln believed the power to restore the Union lay in the executive branch—through presidential pardon. But an emerging faction in the Republican Party, called the Radicals saw the issue differently. These men operated from the premise that the Confederate States had indeed left the Union—committed political suicide at secession—and had to petition Congress for readmission. (Congress approves statehood). And this new president, Andrew Johnson, was determined to follow through with Lincoln’s policies.

Unfortunately, Johnson was by temperament, nothing like Abraham Lincoln. Where Lincoln had a capacity to understand the views of his opponents, and utilize humor and political savvy, Johnson could not. Of prickly character, Andrew Johnson entered the White House possessed by deeply-held rancor against both the South’s Planter Class, and newly freed blacks. This new Chief Executive intended to restore the Union through the use of pardons, then govern through his strict interpretation of the Constitution. Johnson had no use for Radical Republicans, nor their extreme pieces of legislation. Every bill passed through the House and Senate found a veto waiting at Johnson’s desk, including the 1866 Civil Rights Act, and the adoption of the Freedmen’s Bureau. Congress promptly overrode Johnson’s vetoes.

Reconstruction began with a vicious power struggle. And much of the tumult came from Andrew Johnson’s inability to grasp the transformation Civil War had brought to America. While the new president aimed to keep government limited, the Radicals and their supporters knew the bloody struggle had to mean something more—America had fundamentally changed. Nearly 700,000 dead, the emancipation of slavery, the murder of Father Abraham, and a “New birth of Freedom” had heralded an earthquake of change.

But Johnson was blind to this reality, seeing only an overreaching Congress, (Tenure of Office Act) and Constitutional amendments that had gone too far. And so it was a rigid and stubborn Andrew Johnson who eventually found himself impeached by a fed-up House of Representatives. Johnson holding on to his broken presidency by a single Senate vote.

There have been other eras in America’s past that fomented rapid changes. The Revolution to the Constitutional period, the First World War into American isolation, the Vietnam War stirring up protest and social change. All concluding with reactionary presidencies. No less occurred with the 2016 election of Donald Trump.

2008 to 2016 witnessed social change of a new order. Administered by America’s first African-American President, Barack Obama, liberty reached further, bringing about change where once-closeted American’s hid. Gay marriage became the law of the land, upheld by the Supreme Court in Obergefell V Hodges. The trans community found their champion in Bruce, now Caitlin Jenner. Health care became available to those caught in relentless poverty and preexisting conditions. Undocumented young people were transformed into “Dreamers.” And though he didn’t take the Right’s guns, President Obama did successfully direct the mission to nab Osama bin Laden, America’s most wanted man.

So when former students began sending horrified texts to me, their old history teacher on election night, 2016, I gave the only explanation history provided. The Obama years introduced change to America that reactionaries could not stomach. (And yes, racism is certainly a large part of the equation).

So now we deal with a Donald Trump presidency. But, Mr. Trump would be wise to acknowledge and accept what has transpired in the last eight years. The thing about expanding the ‘blessings of liberty,’ is no one is willing to give them back. When push comes to shove, the new president may find himself facing the fate of Andrew Johnson.

Gail Chumbley is the author of River of January and River of January: Figure Eight. Also on Amazon.

It’s been uncomfortable to watch the media coverage from Louisiana about the removal of General Robert E Lee’s statue in New Orleans. As a life-long student of the Civil War the idea of removing reminders of our nation’s past somehow feels misguided. At the same time, with a strong background in African American history, I fully grasp the righteous indignation of having to see that relic in the middle of my city. Robert E. Lee’s prominence as the Confederate commander, and the South’s aim to make war rather than risk Yankee abolitionism places the General right in the crosshairs of modern sensibilities. Still, appropriating the past to wage modern political warfare feels equally amiss.

Robert Edward Lee was a consummate gentlemen, a Virginia Cavalier of the highest order. So reserved and deliberate in his life and career, that he was one of a very few who graduated West Point without a single demerit. Married to a descendent of Martha Washington, Mary Custis, Lee had American stature added to his already esteemed pedigree. (The Lee-Custis Mansion, “Arlington House” is situated at the top of Arlington National Cemetery. And yes, this General was a slave holder, however he appears to have found the institution distasteful).

When hostilities opened in April of 1861, the War Department tapped Lee first to lead Union forces, so prized were his qualities. But the General declined, stating he could never fire a gun in anger against his fellow countryman, meaning Virginians.

On the battlefield Lee was tough to whip, but he also wasn’t perfect, despite his army’s adoration. Eventually, after four years of bloody fighting, low on fighting men and supplies–facing insurmountable odds against General Grant, the Confederate Commander surrendered at Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia.

Meeting Lee face-to-face for the first time to negotiate surrender terms, Ulysses Grant became a little star-struck himself in the presence of the General, blurting out something about seeing Lee once during the Mexican War.

In a letter to his surrendering troops Lee instructed, By the terms of the agreement Officers and men can return to their homes. . .

But Robert E. Lee’s story doesn’t end there.

Despite outraged Northern cries to arrest and jail all Confederate leaders, no one had the nerve to apprehend Lee. And that’s saying a lot considering the hysteria following Lincoln’s assassination, and John Wilkes Booth’s Southern roots. The former general remained a free man, taking an administrative position at Washington College, now Washington and Lee University, in Lexington, Virginia. It was in Lexington that the General died in 1870, and was buried.

Lee led by example, consciously moving on with his life after the surrender at Appomattox. He had performed his duty, as he saw it, and when it was no longer feasible, acquiesced. He was a man of honor. And from what I have learned regarding General Lee, he would have no problem with the removal of a statue he never wanted. Moreover, I don’t believe he would have any patience with the vulgar extremists usurping his name and reputation for their hateful agenda.

This controversy isn’t about Robert E Lee. It’s about America in 2017.

Gail Chumbley is the author of the two part memoir, River of January and River of January: Figure Eight. Also available on Amazon.

So I just read a scathing review of my first book, “River of January.” This reader really hated it, and made a real effort to express her distaste. To say she went out of her way to revile the story doesn’t do justice to the term ‘condemnation,’ and continued to blast me as the author.

So I just read a scathing review of my first book, “River of January.” This reader really hated it, and made a real effort to express her distaste. To say she went out of her way to revile the story doesn’t do justice to the term ‘condemnation,’ and continued to blast me as the author.

So how exactly does a writer react to such a scorcher of a reprimand?

I’d like to get upset and obsess over the two measly stars and every berating word in the post. But I can’t seem to throw myself on that grenade. And much as I’d like to feel mortified and humiliated, I don’t. All that reacting is just too much work–takes too much energy. Besides, if the aim of a book is to elicit an emotional response, then, I suppose, my book has found a kind of success.

Three years ago this review would have destroyed me, almost as if someone had pointed out that my beautiful new baby is actually ugly, and that I’m a blind fool. But as a writer I’ve let go of that kind of perfectionism, and any illusion that I fart roses.

This true story is what it is, and I happen to think it’s damn good, and count myself lucky that it came into my life.

So what now?

I turn on my laptop and compose this blog. Writing is what I do. And some will connect to my voice and identify with this quandary. Others have already clicked cancel.

I suppose that’s why cars come in different colors.

Gail Chumbley is the author of the two-part memoir River of January and River of January: Figure Eight.

Comic skater, Austrian Freddie Trenkler, a cast member in the Sonja Henie Ice Shows, drew countless laughs, and more than a few gasps with his slapstick and death-defying style. This young man, only 27 years old, his identity concealed behind grease paint and rags, ironically shared much in common with his vagabond alter ego.

It was early in the Second World War, and the German war machine blazed across Europe; blitzkrieg overwhelming the Low Countries and France. Freddie’s homeland had fallen much earlier–Nazi occupation of Austria bloodlessly completed in 1938 (think “Sound of Music”). It appears that the Jewish Trenkler had escaped to America, tragically leaving his family to suffer a calamitous fate.

The investigation of papers, pictures, letters, and other mementoes I used in writing River of January, and River of January: Figure Eight, revealed that many of the talented skaters who performed in the Henie productions arrived in America desperate war refugees, who had escaped certain death at the hands of the Nazi’s.

Enjoy this clip of Henie, Trenkler, and the company of ice skaters, (one of whom is Helen Thompson, a subject in both books). However, keep in mind the desperation and harrowing narrative that Trenkler and many others carried to the ice.

In the memoir, “River of January,” Helen, a beautiful and talented dancer, set sail in 1936 to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. She eagerly looked forward to a two week performance at the famed Copacabana Hotel, with an additional two week option to play in Buenos Aires.

On her sheet music for the number, Goody Goody–one of the many songs prepared for this engagement–Helen penciled in her dance steps among the musical notes and rests.

No film survives of Helen Thompson’s April, 1936 performances in South America, but I found this little gem from the same year. (Personal point . . . I think Helen was a better dancer than the girl in this clip).

Happy Friday.

Gail Chumbley is the author of River of January and River of January: Figure Eight and on Amazon.com.