New York

1942

Eileen pounded on the door to Helen’s apartment, down one flight from her own. “Have you ever been ready on time? We’re gonna be late for rehearsal.”

The lock popped and the door squeaked inward. Eileen continued her rant. “That war bond rally is going on in Times Square—the mayor’s there. We’ll have a crowd to get through. Rehearsal, Helen!”

“I’m hurrying, Sis. Keep your socks on. Just trying to find my skating sweater.” Helen fled down the hall to her bedroom.

Throngs of servicemen clad in navy blue or army khaki filled the streets and sidewalks. The Thompson sisters weathered a persistent barrage of catcalls, whistles, and hopeful winks. Red, white, and blue Civil Defense signs loomed along the girls’ route, directing them and the rest of New York to the nearest subway entrance in case of an emergency. Air raid wardens, their helmets bearing the CD insignia, were posted near the signs, ready to take control.

Flags of every description fluttered from office buildings and apartments. From countless apartment windows, silk banners bearing a single blue star notified passersby that a son, brother, or father had enlisted in the service. If the flag happened to field a gold star instead, Helen looked away; it meant a loved one had died battling the enemy. Automatically she thought of Chum, who had left that morning to wing his way to some undisclosed, classified destination. Peering down the narrow brick canyon to the docks, Helen detected the waving lines of maritime flags—navy troopships preparing to ship out. Though distant, those colorful standards added to the vibrant, festive atmosphere of bustling Midtown.

Half a block from Center Theater, Eileen began chuckling. Helen’s thoughts still on the gold stars, she grumbled, “What’s so funny?”

“Well, if I were to actually do everything advertised on the way over here—you know, join the armed forces, plant a garden, donate my girdle to make tires, and sew something for victory—I’d be a gun-toting, green-thumbed, bulging Betsy Ross.” Eileen giggled again.

“Did you miss the one that told you not to talk? Loose Lips Sink Ships? There’s one you could start right now.”

Eileen lunged. But Helen, feeling cheerier, dodged away and sprinted toward the dressing room—big sister in hot pursuit.

Following the success of last season’s It Happens on Ice, Sonja Henie’s new production at Center Theater, Stars on Ice, was several weeks into rehearsal. Both sisters skated four pieces in Act I, including a jitterbug finale titled “Juke Box Saturday Night.” In Act II, they accompanied headliners, blade-dancing the samba and rumba in a Latin-flavored number, “Pan-Americana.” The second act culmination was the all-cast, patriotic “Victory Ball,” with its signature song “Big Broad Smile.”

After rehearsal, the chorus gathered at the Latin Quarter on Forty-Seventh Street, toasting their first round to a successful, productive rehearsal.

“Sometimes I wonder if we’re doing enough for the war effort. Maybe other women are doing more meaningful work.” Helen tapped her nails thoughtfully against her bourbon and water.

“I don’t know, honey,” fellow skater Patsy O’Day answered. “Mayor LaGuardia thinks we’re doing our bit. Did you see the notice he placed in the new program thanking us for keeping up morale?” She sipped her cocktail. “Surely you’ve seen the soldiers and sailors in the seats. Those boys love our show.”

“Chum doesn’t like what you’re doing as it is,” Eileen chimed in. “Wouldn’t he be tickled to hear you’ve volunteered for more?”

Helen ignored her sister’s sarcasm and replied to Patsy, “I’ll have to look at that playbill tomorrow. I’d like to think morale is as important as munitions work, or joining the WAVES. Still, I don’t know how working women manage—especially mothers with small children—with their husbands away in uniform.”

Kay Corcoran, another line skater at the table, nodded in agreement. “I suppose if the woman is lucky, she has a mother or mother-in-law to help her out.”

“Right.” Helen looked thoughtful.

*

After an initial salute, Chum sparked the ignition switch and took off from Floyd Bennett Field, carrying a lieutenant and his aide to nearby Red Bank Field in New Jersey. He and his passengers passed a silent, fifteen-minute hop over New York Harbor. Leveling the nose on his Howard GH-1, Chum smoothly rolled onto the landing strip, slowing to a controllable speed to cross to a navy gray hangar.

A crew chief was watching them from the shade of the facility, and after the passengers departed, he marched over to greet Chum. “Afternoon, sir,” the mechanic saluted. “In case you haven’t heard, Lieutenant, the Japs have done it again.”

“How’s that?”

“Well, sir, they’ve hit us—this time the airstrip on Midway Island. Just came across the wires. Struck Dutch Harbor in the Aleutians too. As we speak, Jap carriers are launching waves of Zeros and Nakajimas.”

Aghast, Chum fought his impulse to leap back into that little Howard, open the throttle, and soar all the way to the Pacific. Forced by duty, and reality, he instead paced the hangar until the two commuters eventually returned. Still, rushing back to New York changed nothing, just another field to pace. The carrier battle raged on thousands of miles away, and no one could do much of anything but wait.

For three anxious days reports trickled in from the Pacific, dispatches that were spotty, vague, and inconclusive. When details emerged of this first-ever clash in the sky, the United States Navy found much to celebrate and, tragically, as much to mourn.

The particulars surfaced days after the attack, presenting a clearer picture of the Battle of Midway. At a morning briefing, base personnel learned firsthand the events surrounding this aerial showdown. “The Imperial Japanese Navy,” began an officer Chum recognized as Lieutenant Commander Kirby, “in an attempt to eliminate US forces on Midway Island, launched multiple airborne assaults. The number of enemy aircraft carriers present in the attack has convinced the Department of War that the Japanese military intended to occupy the island in order to menace US installations farther west in Hawaii.” Kirby paused, somberly measuring his words. “The Empire of Japan has utterly failed in their effort.” The lieutenant commander smiled faintly. “Of the six Japanese carriers under Admiral Yamamoto’s command, four now sit at the bottom of the central Pacific.”

For a moment, the gathering seemed to hold its collective breath, pondering the lieutenant commander’s words. When the full significance sank in, the men jumped to life, roaring in satisfied approval. After the shouting and fraternal backslapping, the crowd finally stood together in a rousing standing ovation.

Kirby couldn’t help but grin at the enthusiastic response, but quickly quelled the celebration with a brief “As you were.” When everyone was seated again, he continued. “Ahem. Yes, this is good news, good news.” Glancing down at his notes and taking a deep breath, he said, “Gentlemen, this great triumph has come at a grim price for the navy. Fellas, we have lost the USS Yorktown. An enemy sub took the old girl down. She was too disabled from the Coral Sea campaign to maneuver away. Our losses so far are sobering—over three hundred casualties at latest count.”

Kirby’s eyes scanned the crowd. “Among the dead, five squadrons of Devastator torpedo bombers from both the USS Enterprise and the USS Hornet. These bombers were utterly blown from the sky while executing attacks on Japanese vessels. The Department of the Navy verified the few who survived the shelling were slaughtered in the water by the enemy rather than rescued. Initial reports from Honolulu indicate that Wildcat fighters, assigned to protect these torpedo bombers, lost all contact, leaving the Devastators hopelessly exposed to Japanese ordnance. Boys, we lost them all, all of our torpedo bombers and pilots—but one, a pilot from Texas.”

The room fell silent, as if there had been no good news at all, no victory in the Pacific. Kirby concluded the briefing with, “Their brave sacrifice made it possible for the rest to find and sink those Japanese carriers.”

Seated among his fellow pilots, Chum shook his head sadly, reminded of a conversation nearly fifteen years before, when he was just a boy—a Seaman, First Class. After a morning of training—of war games—he and a buddy were perched on stools at the base canteen in Panama. Flying his torpedo bomber yards from service vessels had left him unsettled, and he said to his friend, “We approach in low formation, drop our payload and bank, while dangerously showing our undersides to the enemy. We’d be lucky to keep our asses dry, Win. Makes me wonder what desk genius dreamed up this idea. It’s a suicide mission.”

“A suicide mission,” he repeated, in a hopeless whisper, coming out of his reverie.

“Permission to speak, sir,” came a voice from the rear of the hall.

Kirby responded, “Permission granted.”

“How does a sailor go about transferring to the Pacific, sir? With all due respect to our mission here in New York, I want to whip those Japs bad.” Murmurs of agreement swept across the room.

“Fill out the proper paperwork, son.” The lieutenant commander sounded weary. “Complete with your commanding officer’s signature.”

*

Helen quietly turned her key and gently opened the door. Tiptoeing through the dark living room, she saw a stripe of light beaming from under the bedroom door. No wonder it’s quiet—Chum’s awake, no snoring. Entering the lighted room, Helen saw her husband sitting on the bed with an open file folder in his hands. “Honey? Can’t you sleep? I didn’t wake you, did I?”

He smiled her way. “No sweetheart. I thought I would wait up. We haven’t seen each other in a few days. Good crowd tonight?”

Helen smiled back, equally glad to see her husband. “And how! A marvelous audience tonight. Uniforms everywhere—and they gave us a standing ovation.”

“Ha. No kidding! I was part of one of those today myself.” Chum laughed quietly.

“It is so grand to see you awake, Chum. I’ve missed you terribly.”

“Me too.” He paused, choosing his words. “Helen, honey, I stayed up to have a little talk about my . . . about our future. Now, don’t look so panicked,” he added, watching her face drain to pale. “It’s nothing too terrible, honeybunch.” He reached over and patted her arm. “Did you hear the radio reports today—the big brawl out in the Pacific?”

“Of course,” she mumbled, slumping down on the bed. “The radio is always on in the dressing room. No one has the heart to switch it off. We listened to the updates on WCBS. Some of the girls’ husbands have shipped out.” She frowned.

“I want you to know that I am going to talk to Vice Admiral Andrews,” Chum said. “I want . . . I need a transfer to the Pacific too.” Helen stared at her lap. “Honeybunch, please don’t be sad. The navy is fighting back hard . . . I’m not sure how I can explain this so that you’ll understand. Those villains have to be stopped. I owe it to my country, to you, and to myself. Those bastards attacked American soil. Oh, please don’t cry, darling. Please.”

Her voice hitched as she slowly replied, “You told me once that I would have to be brave. You said I needed to trust you, and not to worry. And I have been trying, Chum, really, really hard. I know the country is at war and you have a duty to perform. And, well, I want you to know that I understand how you feel. I—I want to contribute my part too. Even if that only means waiting for you to safely come home and skating to make audiences happy.”

Chum frowned. “You don’t have to keep ska—”

“Yes, I do. It makes me happy too,” she snapped. “People need the distraction now more than ever.”

He sighed—this talk wasn’t going the way he had intended. “Fair enough, Helen. You keep skating. I only wanted to share my intentions, because you need to know. And I am determined to ship out as soon as I can. Helen . . . I want an operating squadron, honey. That means flying fighters—Corsairs, Hellcats, Wildcats, and the like.” He paused a moment in thought. “Frankly, almost everyone on base is bucking for a Pacific transfer after today’s briefing. Look, we—the navy—can whip those devils. We’ve now proven we can beat them in the air.”

Chum took a deep breath before continuing. “I understand that protecting New York is essential, but honestly, the Germans have been restricted. They’re not able to do too much close to shore. We’re in far more danger on the West Coast, and I want in. But”—he shook his head—“first I wanted to talk things over with you . . . and I still have to get the go-ahead from the vice admiral. What he’ll say is anyone’s guess.”

Helen could feel her heart growing numb. With a heavy sigh, she said, “So, you want to go after the enemy.” Her voice became flat. “To fight the Japs in the air. Never mind that you could be killed. Never mind that even if you didn’t die in the air, you’d likely drown in the ocean.” A solitary tear trickled down her cheek.

“Helen, it’s my job. And believe me, sweetheart, I have no particular death wish. Flying is my job, and I think about the risks every time I prepare for takeoff.”

That said, they both grew silent, lost in thoughts words couldn’t phrase. Finally, Chum murmured, “You know, it’s funny—”

“No it’s not,” Helen snapped.

“I suppose ironic is a better word. It strikes me that this argument must be going on all over the country—of wives asking why husbands have to go.”

*

Lieutenant Chumbley remained beside a Lockheed Lodestar, cigar in his teeth, flight plans to Anacostia in his hands. The vice admiral and his aide, Captain Henry Mullinix, had not yet arrived for their flight to Washington and the Department of the Navy. I’m going to ask today. He seems to like me enough to listen. Chum looked up from the documents as the two officers approached, striding side by side to the aircraft.

“Morning, sir. Welcome aboard.” Chum gave a crisp salute as Vice Admiral Andrews climbed into the aircraft.

“Good morning, Lieutenant,” the vice admiral replied in passing. “Let’s keep this plane in the air and absolutely no turbulence. That’s an order.”

“Yes, sir,” Chum said with a chuckle.

“Captain Mullinix.” Chum greeted Andrews’ aide with a salute too, as he climbed up the steps.

“Beautiful day for a flight, wouldn’t you agree, Lieutenant?” Mullinix smiled.

“Yes, sir. The tower reports high, scattered clouds, with unlimited visibility. Will you be joining me in the cockpit, sir?”

“Roger that, Lieutenant.”

Upon reaching altitude, Chum turned the Lodestar over to the captain, a mutually agreed upon arrangement, but only until picking up radio contact for landing. He then relaxed for the hour-plus flight to Washington.

“I’m meeting with Secretary Knox first,” said the vice admiral. “Did I mention that, Captain?”

“Affirmative, sir. A transport vehicle is waiting at the field. We’ll head directly to the navy yard, sir.”

“Very good, Captain.” The vice admiral settled back in the cabin, and with a deep sigh, closed his eyes.

This isn’t the time to ask for any favors, Chum thought, maybe on the way back. There’s time.

The Lockheed descended squarely onto the Anacostia landing strip, soon circling in the direction of the hangar. A large, blue sedan with stenciled white stars on the doors idled nearby, awaiting the high-ranking visitor. Chum grew confused when Andrews, unbuckling his harness, remarked, “Come on with us, Chumbley. Mullinix here needs some company while I breathe the rare air of the Operations conference room.”

“Me, sir?”

“Yes, you, Lieutenant,” Mullinix answered. “I have a set of checkers in my briefcase. These meetings can last forever.”

The three officers stepped into the newer model Cadillac, doors punctually opened by a stiffly saluting chief petty officer. Andrews returned a lackluster gesture to the driver, and the sedan headed toward the city. From the backseat, Chum caught sight of the massive Capitol Building, with the Washington Monument rising in the foreground. But still his thoughts focused on his objective. Maybe I should open the subject with Captain Mullinix first. He’s a real nice gentleman, and could maybe approach Andrews on my behalf.

“How are you at checkers, Lieutenant?” The captain interrupted Chum’s musing.

“Fair, sir, fair. But I haven’t played in a long time.”

“Well, Lieutenant, Mullinix does not extend charity when it comes to checkers, or war for that matter. He plays to win.” Andrews grinned, winking at Henry Mullinix.

Chum smiled in return. “Thanks for the advice, sir.”

The chauffeur braked at the Latrobe Gate outside the navy yard. The driver opened the vice admiral’s door, again formally saluting. The captain reached for his own door handle, stepping out with no pomp. Chum followed suit. Immediately surrounded by subordinates, Andrews walked directly to the entrance, leaving Mullinix and Chum to fend for themselves.

“Let’s head to the canteen, Lieutenant. I’ll call upstairs and let them know where to find us when the vice admiral is ready.”

It wasn’t long before both men were leaning over a Formica table, studying the red and black grid. Mullinix lorded over small stacks of red discs he had captured, while Chum defended the few he had left on the board.

Chum decided to speak up. “Captain, I was hoping for some advice.”

“Now, what more could a pilot with a terrific assignment need?”

“Well, sir, I am rather anxious for active duty . . . out in the Pacific.”

Jumping two of Chum’s checkers, Mullinix smiled sheepishly, snapping the pieces off the board. “You and the rest of the boys in the Eastern Sea Frontier. Most of the paperwork we’re processing comes from fellows just like you—all sailors gunning for Tojo.”

Chum jumped a black disc to crown another.

“Ha. I think you’ve been sandbagging me, Lieutenant.” The captain chuckled. “If you are seriously intending a transfer out to Honolulu, talk to Andrews directly. He’s a reasonable man, and he likes you.” Chum smiled at that. “But that can work against you too, Chumbley.”

Chum’s smile faded. “I don’t understand, sir.”

“The vice admiral is approaching retirement this coming year. He hasn’t been particularly well and is only staying on until the U-boat situation has been satisfactorily eliminated from coastal waters. My guess is that he’s happy with you as his pilot and would want to keep you on his staff. Very hard to predict what Andrews might say. But I will let you in on one tidbit.” Both players unconsciously sat straighter, the game between them temporarily forgotten. “I’m to receive my flags soon, becoming a vice admiral myself.”

After a moment’s pause, Chum felt he should say something. “Congratulations, sir. You have certainly earned the promotion.”

“Yes, thank you, Lieutenant. I will post to the Pacific within the next eight or nine months. The scuttlebutt is I’ll first take command of the Saratoga. As you know, she’s coming out from refitting and heading back to the Solomon Islands. So if you can wrangle a transfer west, I’ll see that you get the duty you want.”

“You would, sir? With an operating squadron?”

“Fighter pilot, huh? I thought you liked this transport-chauffeur service, Chumbley.”

“It is an honor, sir. And I have enjoyed the job enormously. But after Midway . . . well, I too want to settle some scores with those sneaky rascals.”

“Get yourself out to ‘The Show,’ Lieutenant”—the captain sighed—“and I’ll take care of you. How does that sound?”

“That sounds grand, sir.” Chum smiled, relieved.

Resuming their game, Captain Mullinix proceeded to beat Lieutenant Chumbley four games out of six.

River of January: Figure Eight, pps. 200-212.

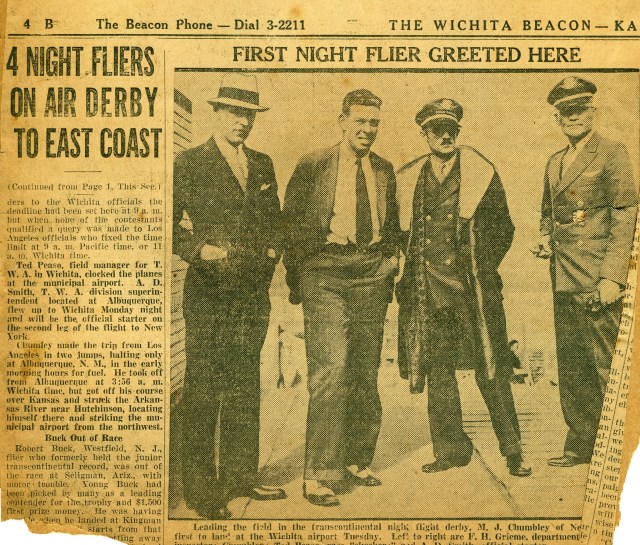

Gail Chumbley is the author of the River of January series.

Also available on Amazon.com

Gail Chumbley

Glendale, California

Glendale, California Wichita

Wichita New York

New York