gailchumbley@gmail.com

I grew up in a union household. And truth be told, the benefits of the Steel Workers Union saw me through childhood, high school, and college, making possible my life’s work as an educator. With a combination of post-war prosperity, cheap hydro power from the Columbia River, and full industrial production at Kaiser Aluminum, my ambitions became possible.

Of course, at the time, I didn’t grasp the real cost paid by earlier generations for my opportunities. That is until I earned my degree in American History and began teaching. What I found in lesson preparation was a grim drama of determined people facing intimidation and violence. Eventually their valor made possible the emergence of America as a global economic power.

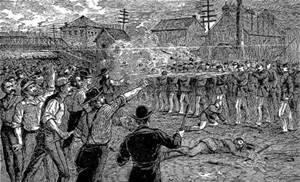

Labor strikes in the 19th Century were especially violent, frequently bathed in bloodshed, betrayal and cruelty. Functioning under the doctrine of “The Gospel of Wealth,” industrialists viewed workers as nothing more than a minor component in mass production. Government at all levels reliably sided with owners to quash any attempts labor made to realize better conditions.

Andrew Carnegie in particular detested unions, and to curb organizing dispersed immigrant workers of different tongues aside one another on the production lines. Language barriers minimized the threat of unionizing.

Another handy device, the Injunction, permitted state governors to legally use State or Federal troops in crushing workers efforts. A governor could claim interstate commerce was impeded, meaning rail carriers couldn’t get mail or goods transported. Once troops were deployed, guns blazing, strikers stood no chance.

One memorable use of the injunction concerned the Pullman Strike of 1894. Employees of the Pullman Palace Car Company endured lives dominated by the company’s powerful owner, George Pullman.

Workers lived in the company town of Pullman, Illinois. All utilities, rents, and other fees were set by the the powerful industrialist, George Pullman himself. Following the onset of the Panic of 1893, Mr. Pullman cut hourly wages, but held the line on municipal fees. Supported by the American Railway Union, (the ARU) workers voted to strike, demanding fairness during the economic downturn.

Strike leaders knew that they must, at all costs, avoid a federal injunction. To bypass any possibility of inviting trouble, the strikers took care that trains continued to move through the state. Rail workers aiding the Pullman strikers detached Pullman Cars, parked them on side tracks, and reconnected the trains.

George Pullman was not amused.

Soon enough the U.S. Attorney General issued the inevitable injunction, permitting federal troops to enter the fray. Some thirty strikers died at the hands of troopers, with many more wounded.

The Pullman Strike ended in government-sponsored violence, but this time the heavy-handed tactics used by Pullman left the general public uneasy. For a country that touted liberty and freedom, the authoritarian power flexed by the industrialist felt rather un-American.

Other labor disputes followed the same pattern; The Haymarket Riot in 1886, the Homestead Strike of 1892, all broken up by militias, soldiers, the police, or hired guns. In 1914 the Ludlow Massacre witnessed the Colorado militia using machine guns to mow down striking miners, women, and children.

Today unions remain controversial. However the role labor has played in America’s development is essential to remember. Labor Unions, in partnership with Capital, built the American middle class, and in return the middle class made the prosperity of this nation possible.

Have a thoughtful Labor Day

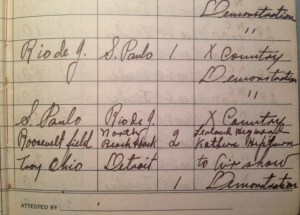

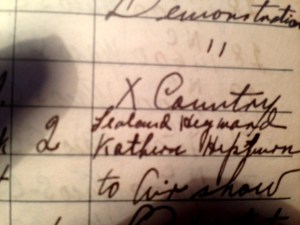

Gail Chumbley is the author of the two-part memoir “River of January,” and “River of January: Figure Eight.” Both titles available on Kindle.