Some social media platforms I’ve read lately insist public schools no longer teach this particular lesson, or that particular subject. And since I was a career history teacher, I want folks to understand that that isn’t necessarily the whole story. If your kids aren’t getting what you believe is important, the problem doesn’t lie in the public classroom. But before I delve into the obstacles, I’d like to describe a slice of my history course.

For sophomores we began the year with the Age of Discovery. As part of this unit students mapped various Native Cultures, placing the Nootka in the Pacific Northwest, and the Seminole in the Florida peninsula. Southwestern natives lived in the desert, while the Onondaga hunted the forests of the Eastern Woodlands. From that beginning we shifted study to Europe, with the end of the Middle Ages. In the new emerging era, Columbus sailed to the Bahamas, and changed the world forever. By the end of the first semester, in December, America had defeated the British in the Revolutionary War, and a new government waited to take shape until the second semester began in January.

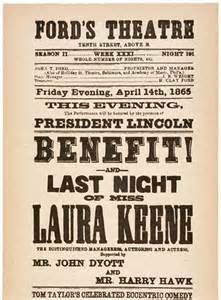

We covered it all. And did the same for the rest of the material, closing the school year with the Confederate defeat at Appomattox Courthouse, and the trial of Reconstruction. And that was only the sophomore course.

The story of America grows longer everyday, and that’s a good thing. It means we’re still here to record the narrative.

The drawbacks? Curriculum writers, in the interest of limited time, have had to decide what information stays and what is cut. For example, pre-Columbian America, described above, was jettisoned in order to add events that followed the Civil War. In short, where we once studied Native American culture in depth, we now focus on the post-Civil War genocide of those same people. What an impact this decision has left upon our young people!

When I was hired in the 1980’s our school district had one high school. Today there are five traditional secondary schools, and also a scattering of smaller alternatives. The district didn’t just grow, it exploded. To cope with this massive influx of students, administrators reworked our teaching schedule into what is called a 4X4 block. Under this more economical system, teachers were assigned 25% more students and lost 25% of instruction time. We became even more restricted in what we could reasonably cover in the history curriculum. (I called it drive-by history.)

On the heels of this massive overcrowding, came the legal mandates established by No Child Left Behind. Students were now required to take benchmark tests measuring what they had learned up to that grade level. Adult proctors would pull random kids out of class, typically in the middle of a lesson, often leaving only one or two students remaining in their desks. These exams ate up two weeks during the first semester, and another two weeks in the Spring.

If that wasn’t enough, politicians, and district leaders began to publicly exert a great deal of favoritism toward the hard sciences, especially in computer technology. So considering the addition of new historic events, overcrowded classrooms, tighter schedules, and mandatory exams, the last thing history education needed was an inherent bias against the humanities.

Public education was born in Colonial New England to promote communal literacy. Later, Thomas Jefferson, insisted education was the vital foundation for the longevity of our Republic. Immigrant children attended public schools to learn how to be Americans, and first generation sons and daughters relished the opportunity to assimilate. In short, enlightened citizenship has been the aim of public education, especially in American history courses.

So basic, so simple.

If indeed, history classes provide the metaphoric glue that holds our nation together, we are all in big trouble. And the threats come from many sides. When our public schools are no longer a priority, open to all, we are essentially smothering our shared past.

Teachers cannot manufacture more time, nor meet individual needs in overcrowded classrooms. And both of these factors are essential for a subject that is struggling to teach Americans about America.

As Napoleon lay dying in 1821, he confessed his own power hungry mistakes, when he whispered, “They expected me to be another (George) Washington.” Bonaparte understood the profound power of the American story.

And so should our kids.

Gail Chumbley is the author of the two volume memoir, River of January and River of January: Figure Eight. Both available at http://www.river-of-january.com and on Kindle.