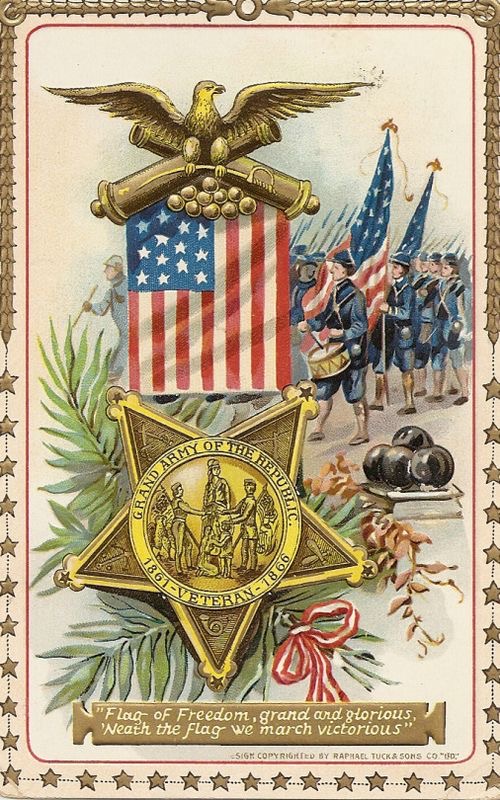

Patriotic symbols, music, and the Pledge of Allegiance recited at a solemn ceremony can be deeply moving. A simple presentation of the flag at a formal function can be awe-inspiring. The lone, austere notes of Taps played at a military funeral elevates a moment into sacred reverence.

The sounds and symbols of American devotion are powerful.

Still, as commanding as recitations, patriotic colors, and America the Beautiful can feel, deeper symbols in our shared history can reveal so much more.

In his book, Washington’s Crossing, historian David Hackett Fischer introduces his volume with a discussion of Emmanuel Leutze’s famous painting of the same name. Fischer guides the reader through elements in the painting, noting passengers figure by figure as they frantically navigate the frozen Delaware River on that long ago Christmas night.

Why is this particular work especially moving? Because at that juncture, December 25, 1776, the Revolutionary War looked to be flaming out after barely a start. Defeat had dogged Washington’s Continentals after being chased off of Long Island, and driven out of New York City the previous summer. As Washington planned his surprise Christmas attack, victorious Redcoats had settled into winter camp in New York City.

Humiliated, Washington knew he had to strike hard and he had to win.

Viewing his situation with the “clarity of desperation” the General ordered an assault on Hessian (German mercenary) held Trenton, New Jersey. The Continental army would have to use the element of surprise fighting against a better armed and better fed opponent. Risky to the extreme, Washington knew we, meaning America, for all time, was dependent upon his actions that night.

As for the painting, the artist depicts freezing soldiers huddled in a boat with more watercraft in the backdrop. From the starboard side, (to the right of General Washington) sits an oars-man, distinctly Black, putting his back into his strokes, ploughing through dangerous ice floes. Behind him, facing forward at the bow, is another swarthy figure, perhaps a Native American. He is desperately kicking ice with his left boot while handling a sharpened pole to break open a passage through the impossible crust. To the foreground an immigrant (a Scot by the look of his hat) studies the river’s surface closely as he pulls forward to port, while another behind him, in fisherman gear, studies the treacherous water. Others are made up of rustics, one at the tiller, along with a wounded passenger.

General Washington centers the painting as he is the central figure of the drama. Behind the General is Major James Monroe, and another rugged frontiersman by the looks of his garb. Both men are grasping a 13-star (Betsy Ross) flag, in a grip that elicits an attitude of determination and desperation, with perhaps a bit of warmth. Below both flag bearers sits a WOMAN, yes, a woman pulling her oar with an analytic eye upon the clotting water.

Black, Native, white, immigrant, the highborn, the humble, men and women, yesterday, today, and the future: all of our American lives balanced on the gamble played that night in 1776.

The point I believe Leutze is trying to convey is that we all don’t have to be the same. No one has to agree on the details of our beliefs to ride on that boat. The truth is Americans all have and had different realities and ambitions: differing views of liberty. Still, all onboard had to carefully respect each other’s space and not overturn that fragile vessel, Liberty, for we must stay afloat and row in the same direction. It is in all our interests to do so.

And that metaphor of America, that boat, tested our resolve on one of the nation’s most critical nights. Inspiration doesn’t come any better than from Leutze’s allegorical Washington’s Crossing.

Gail Chumbley is the author of the two-part memoir, River of January, and River of January: Figure Eight. Chumbley has also penned two stage plays, Clay, and Wolf By The Ears, concerning the life of Senator Henry Clay, and an in-depth examination of the beginnings of American slavery. Gail is currently working on another piece, Peer Review, best described as Dickens A Christmas Carol meets presidential history.